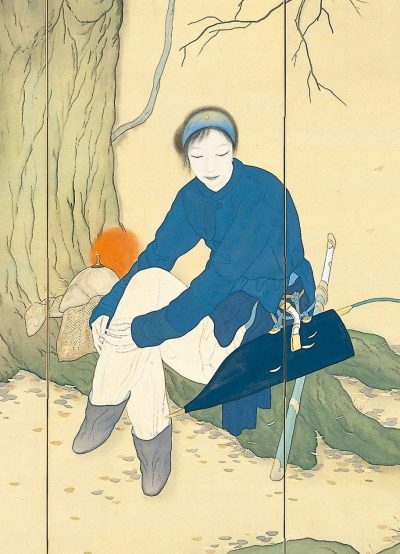

The picture of Hua-Mu Lan enlisting as a soldier instead of her father, was painted by Pan-Li shui on Dalongdong Baoan Temple

The picture of Hua-Mu Lan enlisting as a soldier instead of her father, was painted by Pan-Li shui on Dalongdong Baoan Temple

Pow951753 / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

The history

No-one knows who wrote the folk song, Ballad of Mulan, or even when. It was most probably composed during the 5th century AD, but the earlier recorded version shows up in the latter half of the 6th century, in the Musical Records of Old and New, a selection of works curated by a monk, Zhijiang. This version does not provide her with a surname; it was only much later, in a 17th-century adaptation by playwright Xu Wei, that “Hua” became accepted as her family name. But, while the conflict with the nomadic barbarians appears to be real, there is much doubt as to whether Mulan was a genuine historical person, or a fictional creation.

It probably doesn’t matter: the myth matters considerably more than the reality, especially at this distance in history. It probably helps that the story, as told in the original song, is not particularly heavy on detail. In English translation, it’s less than 500 words in total, so is more of a brief synopsis, an outline of the characters and plot. This allows each adaptation to create a version of Mulan in their image, moulding the heroine to their own ends.

For example, take Xu Wei’s version, The Heroine Mulan Goes to War in Her Father’s Place. While still relatively terse, perhaps only 20 pages, it adds scenes which show Mulan unbinding her feet before going to war, while all but omitting her battles. Foot binding was a symbol of femininity at the time, and so her tying them back up on her return home, symbolizes her willingness to accept a normal social role. Though it may also have been titillating to the male audience of the time. This is probably Quentin Tarantino’s favourite version of the story.

The play ends with Mulan taking part in an arranged marriage. It’s perhaps this aspect where those retelling the story have most latitude, as the original source says little about Mulan’s life after her return. Consequently, there are a broad range of outcomes. In some, she even commits suicide, such as the version of the tale told in Women Generals by Zhu Guozhen.

When the royal court finally heard about Mulan’s true nature, Emperor Yang offered her a position in the royal harem. Again, Mulan declined, saying, “Your humble servant is unworthy of this honor.” When the emperor tried to take her by force, and she realized that she could not resist his demands, she ended her own life.

Much as the story of Robin Hood can be told as a parable against contemporary corrupt leaders, so Mulan’s bravery and loyalty can provide a heroic figure to contrast with current events. This applies to cinematic versions of the story, as well as the written, though it can work for the authorities as well. 1939’s Mulan Joins the Army, is unabashedly pro-military and jingoistic, as its title suggests. It’s unsurprising – China was at war with Japan at the time – but stressing the benefits to be gained by soldiers was a helpful recruitment tool. More on this topic below.

Much as the story of Robin Hood can be told as a parable against contemporary corrupt leaders, so Mulan’s bravery and loyalty can provide a heroic figure to contrast with current events. This applies to cinematic versions of the story, as well as the written, though it can work for the authorities as well. 1939’s Mulan Joins the Army, is unabashedly pro-military and jingoistic, as its title suggests. It’s unsurprising – China was at war with Japan at the time – but stressing the benefits to be gained by soldiers was a helpful recruitment tool. More on this topic below.

Political considerations impacted both Disney versions as well. The original came about, partly in an attempt by Disney to repair its relationship with China. This had been hurt by Martin Scorsese’s 1997 film Kundun, which was condemned by the Beijing government for its depiction of Tibet and its spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, as well as the Chinese Communist Party’s crushing of local traditions. This led to a ban on Disney movies in China, which lasted until February 1999, when the first film to benefit was… Mulan, the studio’s retelling of a local legend. While that film was already in production when controversy struck Kundun, it allowed Disney to position itself as a promoter of state-sanctioned Chinese culture. It was only somewhat successful, though this was in part because the lengthy delay allowed pirate copies to impact box-office.

The 2020 live-action version was even more directly targeted at the local audience, with a largely Chinese cast. Even more pointedly, the Wall Street Journal reports that “To avoid controversy and guarantee a China release, Disney shared the script with Chinese authorities while consulting with local advisers.” The resulting story subtly (and, in some ways, not-so subtly) changes the focus from the right to self-determination for the individual, to the need for self-sacrifice for the greater good of the state. Yet, it doesn’t seem to have particularly worked. The film took only $23.2 million on its opening weekend in China. For comparison, back in 2017, Resident Evil: The Final Chapter opened with $91.7 million.

It’s interesting to watch the various versions, and see how they have built open the sparse foundations provided by the song. Elements are added or changes as needed, and they then become potential candidates for inclusion in subsequent versions. For example, among the variations on the theme which have been played: are Mulan’s parents aware or not of her deception? Over what time-frame do things take place? Is there a scene where she gets drunk and nearly reveals her gender? What about a bathing one? Does she stumble across the site of an enemy massacre? What’s included tells us much about the intent of the makers.

But let’s go back to the beginning. Below, is a translation of the original source material, which is worth a read, both for what it contains, and what it doesn’t.

The poem

The sound of one sigh after another, as Mulan weaves at the doorway.

The sound of one sigh after another, as Mulan weaves at the doorway.

No sound of the loom and shuttle, only that of the girl lamenting.

Ask her of whom she thinks, ask her for whom she longs.

“There is no one I think of, there is no one I long for.

Last night I saw the army notice, the Khan is calling a great draft –

A dozen volumes of battle rolls, each one with my father’s name.

My father has no grown-up son, and I have no elder brother.

I’m willing to buy a horse and saddle, to go to battle in my father’s place.”

She buys a fine steed at the east market; a saddle and blanket at the west market;

A bridle at the south market; and a long whip at the north market.

She takes leave of her parents at dawn, to camp beside the Yellow River at dusk.

No sound of her parents hailing their girl, just the rumbling waters of the Yellow River.

She leaves the Yellow River at dawn, to reach the Black Mountains by dusk.

No sound of her parents hailing their girl, just the cries of barbarian cavalry in the Yan hills.

Ten thousand miles she rode in war, crossing passes and mountains as if on a wing.

On the northern air comes the sentry’s gong, cold light shines on her coat of steel.

The general dead after a hundred battles, the warriors return after ten years.

They return to see the Son of Heaven, who sits in the Hall of Brilliance.

The rolls of merit spin a dozen times, rewards in the hundreds and thousands.

The Khan asks her what she desires, “I’ve no need for the post of a gentleman official,

I ask for the swiftest horse, to carry me back to my hometown.”

Her parents hearing their girl returns, out to the suburbs to welcome her back.

Elder sister hearing her sister returns, adjusts her rouge by the doorway.

Little brother hearing his sister returns, sharpens his knife for pigs and lamb.

“I open my east chamber door, and sit on my west chamber bed.

I take off my battle cloak, and put on my old-time clothes.

I adjust my wispy hair at the window sill, and apply my bisque makeup by the mirror.

I step out to see my comrades-in-arms, they are all surprised and astounded:

‘We travelled twelve years together, yet didn’t realise Mulan was a lady!'”

The buck bounds here and there, whilst the doe has narrow eyes.

But when the two rabbits run side by side, how can you tell the female from the male?

The adaptations

Below, you’ll find our reviews of some of the feature versions of the story which have been told over the years: they’re in chronological order of the film in question. For context, the review of the Disney animated version was from back in 2004 (I’ve been at this too long!); the 2009 live-action film was reviewed in 2012; the others are new. This is by no means comprehensive: some, such as the first movie version, 1927’s Hua Mulan Joins the Army, appear to be lost, while others… Well, if you can get through more than five minutes of Orlando Corradi’s animated version – which, interestingly, came out before the Disney one, in 1997 – you are made of sterner stuff than I, dear reader.

Mulan Joins The Army

By Jim McLennan★★★

“She’s in the army now…”

Y’know, considering this is now more than eighty years old, this was likely better than I expected. Chen makes for a solid and engaging heroine, right from the start, when she tricks the residents of a nearby village, who demand she hand over the proceeds of her hunting [I am hoping the dead bird which plummets to the ground with an arrow through it, less than three minutes in, was a stunt avian…]

Y’know, considering this is now more than eighty years old, this was likely better than I expected. Chen makes for a solid and engaging heroine, right from the start, when she tricks the residents of a nearby village, who demand she hand over the proceeds of her hunting [I am hoping the dead bird which plummets to the ground with an arrow through it, less than three minutes in, was a stunt avian…]

Equally quickly, we begin to see wrinkles in the storyline, which might be unexpected if you have only seen the Disney versions. The first of these, is that Mulan’s deception here takes place with the agreement of her parents. She doesn’t sneak out with her father’s sword in the middle of the night, to take his place in the conscripted army of the Emperor. Her martial tendencies have been at least tacitly encouraged: according to Mom, it was her father who taught her the use of the bow and spear, since she was a little girl.

Mind you, with Mom saying things like, “Dying on the battlefield is much more glorious than dying at home,” no wonder Mulan comes up with the idea of being Dad’s stand-in. Her parents aren’t exactly happy about it, but they do understand the situation, and accept her decision. This pro-military stance is something which runs through much of the film. Before leaving, Mulan says, “Father, I thank you for teaching your daughter how to fight. You are allowing me to fulfill my duty to the country, and my filial duty to you… You have granted your daughter her dearest ambition – to be of some use to her country.”

Given this came out during the Japanese occupation of China, the theme of “Let’s all unite and do our part to defeat the invaders” seems rather brave. Though oddly, when the film was released, it provoked riots in which copies of the film were burned, due to rumours the director had collaborated with the Japanese to get it made.

The second most obvious change is the time-frame. Mulan doesn’t just knock off the barbarians and return home in a month or two. No, she goes career, eventually rising to become marshal of the army, due to her bravery and smarts, as well as helping uncover a double-agent high up in army command. It’s twelve years before she is able to see her parents again, though she looks suspiciously similar to when she left. It likely helps she doesn’t have to rise through the ranks, being able to inherit her father’s position as his “son.”

While the action quotient is, unsurprisingly, fairly low, there’s a cool bit where she goes on reconnaissance, dressed as a woman – so, a woman disguised as a man, pretending to be a woman. Got it. She is caught by two barbarian guards, but bursts into song, distracting them long enough to stab them to death. That’s a first, I think. Though I could have done without the further musical interlude at the end, the romance between Mulan and her long-time friend Liu Yuandu (Xi) is never over-powering, and is more a sidelight than the main attraction.

Obviously, its age and origin have to be taken into account, and expecting modern-day production values would be silly. Yet, allowing for everything, I’ve been considerably less entertained by many more recent films. The whole thing is now on YouTube, with English subtitles, and should you be interested, is embedded below.

Dir: Bu Wancang

Star: Chen Yunshang (Nancy Chan), Mei Xi, Han Langen, Liu Jiqun

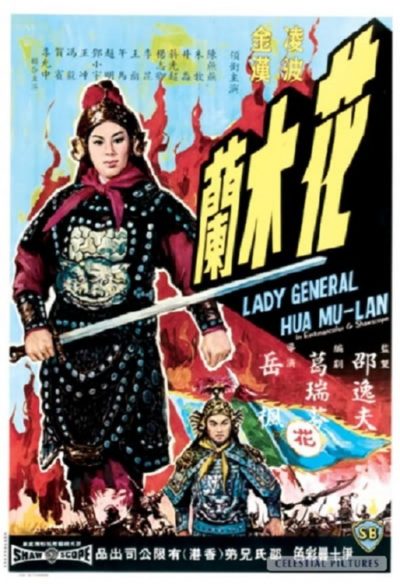

Lady General Hua Mu-lan

By Jim McLennan★½

“Cinematic morphine.”

I probably should have done a bit more research before adding this to the list of versions for review here. I saw a sixties movie made by Shaw Brothers with that title, and presumed there would be kung-fu. Boy, was I wrong. There’s about one significant scene, which pits Mulan (Po) and some of her new army colleagues against each other. And that’s it. Oh, there is a battle between Imperial and invading forces. This might have contained some action, but was so poorly photographed – mostly due to incredibly bad lighting – that it was impossible to tell. What there was, instead, was singing.

I probably should have done a bit more research before adding this to the list of versions for review here. I saw a sixties movie made by Shaw Brothers with that title, and presumed there would be kung-fu. Boy, was I wrong. There’s about one significant scene, which pits Mulan (Po) and some of her new army colleagues against each other. And that’s it. Oh, there is a battle between Imperial and invading forces. This might have contained some action, but was so poorly photographed – mostly due to incredibly bad lighting – that it was impossible to tell. What there was, instead, was singing.

Lots of singing.

For this is as much an action movie, as Hamilton was a documentary about the Revolutionary War. Now, I’ve no problems with musicals per se. I’m just more Rodgers and Hammerstein than Stephen Sondheim: I like something I can whistle. This sounds more like notes being strung together at random, and when an apparently jaunty tune is accompanied by lyrics more befitting Scandinavian death metal (“They burn, they slaughter, they rape, they catch”) the effect is even more dissonant than the score.

If I’d looked up Wikipedia beforehand, I’d have seen this described this as a “Huangmei opera musical.” Huangmei opera, in case you didn’t know (and I certainly didn’t), is a bit like the better known Peking opera. Except, per Wikipedia, “The music is performed with a pitch that hits high and stays high for the duration of the song.” To my untrained Western ear, this meant the musical numbers basically sounded like our cats, demanding to be fed. I don’t like five minutes of that kind of thing (especially at 5:30 in the morning). I can now state confidently, I do not like it at feature length either.

This actually starts reasonably well. Initially, Mulan conspires with her cousin Hua Ming (Chu) and sister to carry out her plan. This ends after her alternate persona tries to spar with her father, though he ends up giving his blessing. Ming accompanies her into military service, and they rise through the ranks. Mulan begins to have feelings for her superior officer, General Li (Chin). He likes her too, impressed with her intelligence and courage… and this Mulan would be a fine match for his daughter. #awkward. Cue mournful singing, naturally.

But the lack of dramatic conflict is what really kills this, stone dead. Mulan’s parents are largely on board with her decision. The invaders are never established as a particular threat. And everyone is remarkably chill with discovering the person they’ve known for over a decade has been deceiving them on an everyday basis. The complete absence of tension explains the tag-line at the top. Obviously, I am not the target audience for Huangmei opera. That’s fine. However, I’ve enjoyed plenty of films for which I am not the target audience, and I suspect this fails to travel well, for a variety of reasons.

Dir: Feng Yueh

Star: Ivy Ling Po, Han Chin, Kam-Tong Chan, Mu Chu

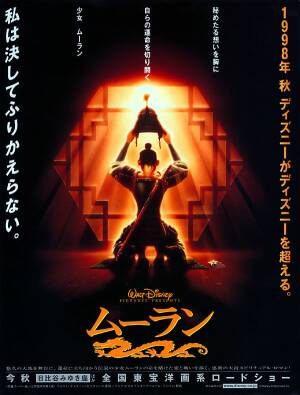

Mulan (animation)

By Jim McLennan ★★★★½

★★★★½

“Here be drag-ons…”

D

D isney movies are not the usual place to find action heroines: their classic woman is a princess, who sits in a castle and waits for someone of appropriately-royal blood to come and rescue her from whatever evil fate (wicked stepmother, poisoned spinning wheel, etc.) that has befallen her.

isney movies are not the usual place to find action heroines: their classic woman is a princess, who sits in a castle and waits for someone of appropriately-royal blood to come and rescue her from whatever evil fate (wicked stepmother, poisoned spinning wheel, etc.) that has befallen her.

The first inklings of a change to this traditional attitude came in 1991 with Beauty and the Beast, where Belle was an independent-minded young lady who rejected the advances of the handsomely square-jawed hero, because he was an idiotic jerk. Unfortunately, the moral was somewhat diluted by the end when – and I trust I’m not spoiling this for anyone – the Beast turns into a rather convincing facsimile of said handsomely square-jawed hero. So, looks are everything, after all… Much more successful was their 1998 attempt, Mulan, recently released for the first time on DVD, which took a traditional Chinese legend about a girl who dresses as a man to join the army, and converted it into the traditional Disney animated feature format, complete with songs and amusing sidekick. Given the studio’s previous track record (hey, why bother paying writers to come up with new stories, when there’s public domain ones to rape?), qualms here are understandable. Perhaps most memorably, Disney gave Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid a happy ending, though turning Quasimodo into a lovable Happy Meal probably comes close – that whirring sound you hear is Victor Hugo spinning in his grave.

And, yes, liberties were taken, though to be fair, you expect this in any screenplay – especially one whose story originally appeared in a poem written by an anonymous Chinese author around the 5th or 6th century AD. [The poem also appears on the DVD, but without any attribution or context; you’d be forgiven for thinking it was written by a Mousketeer] From here sprang a whole raft of tales, with different eras, locations or surnames, largely dependent on the author’s feelings, but having several common threads. The story takes place over more than a decade, and Mulan’s identity isn’t discovered until she has finally returned home and resumed her normal life.

There’s also no threat of execution when her deception is found out – Chinese culture may perhaps actually have a more tolerant approach to such things, though this is admittedly going only by the likes of Peking Opera, and a good chunk of Brigitte Lin’s career. And, of course, both the romantic angle and amusing sidekick were modern additions. This contrasts sharply with one version of the original, which has the Emperor hearing of Mulan’s exploits, and demanding she becomes his concubine. Mulan commits suicide in preference to this fate, an ending that, for some reason, didn’t make it into the Disney adaptation…

There’s also no threat of execution when her deception is found out – Chinese culture may perhaps actually have a more tolerant approach to such things, though this is admittedly going only by the likes of Peking Opera, and a good chunk of Brigitte Lin’s career. And, of course, both the romantic angle and amusing sidekick were modern additions. This contrasts sharply with one version of the original, which has the Emperor hearing of Mulan’s exploits, and demanding she becomes his concubine. Mulan commits suicide in preference to this fate, an ending that, for some reason, didn’t make it into the Disney adaptation…

Perhaps the surprising thing is that there haven’t been more movie adaptations of the story – contrast the literally hundreds of movies based on Wong Fei-Hung. There have been a couple, most notably 1960’s The Lady General Hua Mu Lan, directed by Yue Fung, and starring Ling Buo as Mulan (real-life husband Jing Han played General Li). Before that was Maiden in Armor starring Nancy Chan, made in 1937, largely as propaganda to rally the Chinese against the Japanese. The most recent version was in 1999; Yang Pei-Pei’s 48 episode TV series starred Anita Yuen as Mulan [photo, right]. However, over the past couple of years, no less than three versions have been rattling around in development hell. The most eagerly anticipated one stars Michelle Yeoh as Mulan, with Chow Yun-Fat co-starring. The director is uncertain (Peter Pau and Christophe Gans are most often mentioned) and production still hasn’t started, even though it was announced back in July 2001; recent reports now have it scheduled to begin filming early next year.

Stanley Tong has also been working on The Legend of Mulan; the original plan was to shoot this in English, with Lucy Liu and The Rock as Mulan and the Hun general respectively, but this may have fallen through; with Tong now working on the next Jackie Chan film, this one seems to be on the back-burner. Finally, a Korean version, with either Jeon Ji Hyun (My Sassy Girl) or Zhang Zi-Yi, was scheduled, but not much has been heard about this lately. The Disney version, on the other hand, just came out on DVD for the first time – in part, I suspect, to act as marketing for the forthcoming, inevitable Mulan II. The trailer for the sequel is on the Mulan DVD, but Lady and the Tramp II, The Little Mermaid II, The Hunchback of Notre Dame II and Aladdin II should give you an idea of how wonderful Mulan II will be. [It’s going straight to video, of course, but it does at least have Ming-Na Wen. No Eddie Murphy though.]

That’s a shame, because the original still has a great deal to offer. Unlike many Disney films, the songs don’t bring proceedings to a grinding halt and are notably absent from the second half of the film. Indeed, the transition is deliberately abrupt: a band of happy, singing warriors is stopped mid-verse when they come across a burnt-out village which the Huns have exterminated (right). It’s a simple, but highly effective moment, where silence says a lot more than any words. [At one point a song for Mulan about the tragedy of war was considered, but this was dropped, along with Mushu’s song, Keep ‘Em Guessing – both decisions which can only be applauded.]

That’s a shame, because the original still has a great deal to offer. Unlike many Disney films, the songs don’t bring proceedings to a grinding halt and are notably absent from the second half of the film. Indeed, the transition is deliberately abrupt: a band of happy, singing warriors is stopped mid-verse when they come across a burnt-out village which the Huns have exterminated (right). It’s a simple, but highly effective moment, where silence says a lot more than any words. [At one point a song for Mulan about the tragedy of war was considered, but this was dropped, along with Mushu’s song, Keep ‘Em Guessing – both decisions which can only be applauded.]

Obviously, in terms of action, it’s hamstrung by the G-certificate (though the British censors insisted on a headbutt being removed to get the equivalent ‘U’-rating), but allowing for this, it’s still got some exciting scenes, and the first encounter between Mulan and the Hun army is fabulous by any measure. It also avoids the pitfall of many a Disney film – making the villains more memorable than the main characters. [Everyone remembers Cruella DeVille from 101 Dalmatians; but can you name the hero?] Here, Shan-Yu is almost a caricature, but does what’s necessary quickly, allowing the other characters to be developed more completely, and compared to other Disney heroines, Mulan may be the most well-rounded human being.

Of course, Eddie Murphy comes close to stealing the show as demoted family guardian, Mushu. Unlike Shrek, where the competition for laughs with Mike Myers was painfully clear, Ming-Na Wen is content to be the straight “man”, and the film benefits as a result. Murphy’s accent is entirely anachronistic, naturally, but that’s half the fun – interestingly, the American DVD offers the option of a Mandarin soundtrack, which is a nice option. We did try it for a bit, but the Chinese Mushu just didn’t have the life and energy of Murphy, and we soon switched back. [HK singer CoCo Lee plays Mulan, while Jackie Chan is the voice of Shang in both this and the Cantonese versions] The tunes are perhaps not quite “classic” Disney, in the sense that they don’t stay in your brain for years after, to explode at the most inappropriate moments. They’re still fairly hummable though, and Jerry Goldsmith’s Eastern-tinged score compliments the similarly Oriental-flavoured animation well. The makers clearly did a lot of research, thought it does have to be said, the film does not exactly portray Chinese culture in a particularly good light; Mulan, the heroine, is shown as rebelling against it in almost every way. One reviewer describes its basic theme as, “a woman with western values overcoming the oppression of a backwards Chinese civilization.” Ouch.

However, personally, I’d say the value of having a clearly non-Caucasian heroine (a first for any Disney film) outweighs relatively minor quibbles about subtext. It may be the last great hand-drawn animated feature from the studio which invented the genre, and all but defined it for sixty years, so I have absolutely no hesitation in recommending this as an empowering and highly entertaining tale for children – of any age, but especially those too young to read subtitles. There aren’t many action heroine films our entire family loves, but Mulan is definitely high on the list.

However, personally, I’d say the value of having a clearly non-Caucasian heroine (a first for any Disney film) outweighs relatively minor quibbles about subtext. It may be the last great hand-drawn animated feature from the studio which invented the genre, and all but defined it for sixty years, so I have absolutely no hesitation in recommending this as an empowering and highly entertaining tale for children – of any age, but especially those too young to read subtitles. There aren’t many action heroine films our entire family loves, but Mulan is definitely high on the list.

Dir: Tony Bancroft and Barry Cook

Star: Ming-na Wen, Eddie Murphy, B.D.Wong, Soon-Tek Oh

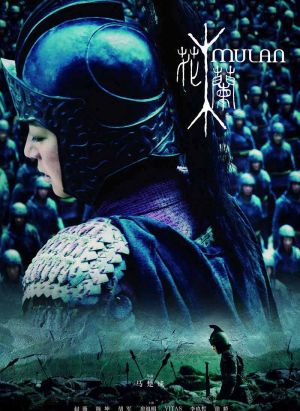

Mulan (2009)

By Jim McLennan★★★½

“Joan of Arc, without the religion. Or stake.”

Inspired by the same poem as Disney’s much-loved feature, this has the same basic idea – a young woman impersonates a man in order to save her father from being drafted in the army. However, this takes a rather different approach, being much darker in tone, not that’s this is much of a surprise, I guess. It’s also a lot longer in scope, with Mulan (Zhao, whom you may recognize as the heroine/goalkeeper from Shaolin Soccer), rather than fighting a single campaign, becoming a career soldier and rising through the ranks as a result of her bravery in battle, eventually becoming a general, tasked with defending the Wei nation from the villainous Mendu (Hu). He has killed his own father in order to take control, and has united the nomadic tribes of the Rouran, amassing an army of 200,000 to invade Mulan’s home territory. She comes up with a plan to lure him into a trap, but when she is betrayed by a cowardly commander, things look bleak indeed for Mulan and Wentai (Chen), one of the few who know her secret.

Inspired by the same poem as Disney’s much-loved feature, this has the same basic idea – a young woman impersonates a man in order to save her father from being drafted in the army. However, this takes a rather different approach, being much darker in tone, not that’s this is much of a surprise, I guess. It’s also a lot longer in scope, with Mulan (Zhao, whom you may recognize as the heroine/goalkeeper from Shaolin Soccer), rather than fighting a single campaign, becoming a career soldier and rising through the ranks as a result of her bravery in battle, eventually becoming a general, tasked with defending the Wei nation from the villainous Mendu (Hu). He has killed his own father in order to take control, and has united the nomadic tribes of the Rouran, amassing an army of 200,000 to invade Mulan’s home territory. She comes up with a plan to lure him into a trap, but when she is betrayed by a cowardly commander, things look bleak indeed for Mulan and Wentai (Chen), one of the few who know her secret.

Initially, I was rather unconvinced by Zhao who, being in her mid-30s, is a tad old to be playing the dutiful daughter. But given the longer view taken by the movie, the casting makes sense, and she ends up fitting into the role nicely; there’s a steely determination which develops over the course of the film, and by the end, you can see why she has become a commander. That’s one of the themes of the movie: duty, contrasted with the terrible losses war can inflict on a personal level, Mulan being largely powerless to watch as almost all her friends end up dying in battle. “I’ve fought battle after battle,” she says, “Lost one after another of my brothers, I really don’t want to fight any more.” There’s almost a neo-totalitarian implication to the final message, however, which suggests that everyone – even those who have sacrificed everything already – need to put aside their personal interests for the greater good of the state.

There’s a nice balance between the action and emotional aspects, but Zhao doesn’t actually do much in the latter department after the battle which gets her noticed. She’s broken out of army jail to take part, after confessing to stealing a jade pendant, in order to avoid a strip-search [death before dishonour]. After that, she’s more a leader than an actual fighter: heavy is the head that wears the general’s helmet is the moral here, and it’s driven home effectively enough, thanks mostly to Zhao’s solid performance.

Dir: Jingle Ma

Star: Zhao Wei, Chen Kun, Hu Jun, Jaycee Chan

Mulan (2020)

By Jim McLennan ★★★

★★★

“The most expensive straight-to-video release ever.”

Okay, that’s perhaps a little unfair. When this began filming, back in August 2018, who could have predicted that the summer this year would be all but wiped out [seriously: the second quarter in North America, the total box-office was $4.8 million. Last year, the same period brought in $3.3 billion] As films scrambled to re-establish themselves, finding new slots for hopeful release, post-pandemic, there were inevitable casualties, as some were left without seats when the music stopped. Probably the biggest loser was the latest of Disney’s live-action adaptations, based on the beloved animated feature of 1998.

Despite a budget estimated at $200 million, it had the misfortune to be originally scheduled just before everything went to hell. Indeed, it even had its world premiere on March 9th, but the broader release was bumped, first to July, then August, before it was cancelled as a theatrical release in the United States, instead being used as a pay-per-view title on Disney’s streaming service, Disney+. Matters were likely not helped by online comments made by the film’s star against the anti-Chinese protests in Hong Kong, which triggered calls for a boycott of the film. It was notable, even before the film was commercially available, that the Google ratings of the film were largely 1/5 or 5/5, as competing armies of review bombers sought to skew the results to their desired outcome.

As with most things which provoke extreme reactions, the reality sits somewhere in the middle. This isn’t the first live-action adaptation of the legend I’ve seen. There was previously a 2009 adaptation from Hong Kong, starring Wei Zhao as Hua Mulan. Our review of it concluded, “There’s a nice balance between the action and emotional aspects… Heavy is the head that wears the general’s helmet is the moral here, and it’s driven home effectively enough, thanks mostly to Zhao’s solid performance.” It merited 3½ stars, a little above this, though that may simply be due to the newest version being more directly compared to the animated version. That’s inevitable, especially when Disney have sampled songs from it into the new soundtrack.

And make no mistake: I love the animated version: to me, it’s the best of the “new wave” of Disney features which began with Beauty and the Beast. It has a huge emotional range, perhaps more than any other Disney film outside Pixar, and can switch on a dime, going from cheerful song to grim destruction without jarring. I will also say, this is the first I’ve seen in Disney’s live-action adaptations of their animated catalog. All the others seemed entirely redundant, but this one seemed to offer scope for a different take on the subject. It does deliver on this expectation, but I can’t help feeling that, overall, more was lost here than gained.

And make no mistake: I love the animated version: to me, it’s the best of the “new wave” of Disney features which began with Beauty and the Beast. It has a huge emotional range, perhaps more than any other Disney film outside Pixar, and can switch on a dime, going from cheerful song to grim destruction without jarring. I will also say, this is the first I’ve seen in Disney’s live-action adaptations of their animated catalog. All the others seemed entirely redundant, but this one seemed to offer scope for a different take on the subject. It does deliver on this expectation, but I can’t help feeling that, overall, more was lost here than gained.

The live-action version certainly doesn’t manage the same breadth of emotion. For example, there are moments here which feel like they should be comic – except they’re just not funny. It’s a Very Serious tale [capitals used advisedly], almost to the point of solemn, with this Mulan at times feeling like a duty-driven automaton. It’s a thoroughly different portrayal, considering the story is almost identical. When the Chinese empire is threatened by Mongolians, under Böri Khan (Lee), the Emperor requires each family to provide one man to the army. Rather than succumb to an arranged marriage, Mulan (Liu) takes the place of her father in the draft. Though her ruse is eventually discovered, Mulan proves key to the defeat of the invaders.

This edition, however, has no musical numbers, no comic relief sidekick dragon and no romantic interest for Mulan in the shape of her commander [this was apparently excised for #MeToo reasons, but doing so ended up angering some in the GLBTQ community. Yes, apparently, Mulan/Li Shang gay ‘shipping is a thing. Who knew?] Instead, it adds Xianniang (Li), a sorceress who assists Khan, but who sees in Mulan a younger version of herself – someone forced to repress their abilities and true nature, in compliance with social norms. Their scenes have some potential in terms of dramatic conflict, but there just isn’t enough screen time for their relationship to have much impact.

It’s something the film needs, to overcome what it otherwise a distinct lack of emotion. Crouching Tiger showed a martial arts film can still connect to the viewer’s heart, and this never comes particularly close to doing so. The heroine here largely operates in a vacuum, as far as relationships go, even after her true identity is revealed. This may have been an issue recognized by the makers of the animated version. The presence of Eddie Murphy’s Mushu there now makes a great deal of sense, providing that necessary outlet, and acting as a foil for the heroine throughout her journey.

Yet, boy (or rather, girl), does it look nice. Outside of a couple of moments of slightly flaky CGI early on, such as the young Mulan jumping from a roof, this is a beautiful spectacle, clearly influenced by the likes of Hero in its use of colour. The action is well-choreographed; having Yen as leader of the Imperial army doesn’t exactly hurt, even if you wonder why he can’t defeat the invaders single-handed. After all, I’ve seen Ip Man… [Also in supporting roles, Jet Li plays the Emperor, and the matchmaker is Cheng Pei Pei, of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon fame, but more relevantly here, was one of the first Hong Kong action heroines, in 1966’s Come Drink with Me] I’m definitely sorry we were robbed of the chance to see this on a big screen, as that’s the scale it deserves.

Most of the above was written within 24 hours of watching it, but now, with less than 72 hours having passed, I am seriously struggling to recall many particularly memorable moments. Overall, I can’t say I felt like the two hours were wasted, and it’s perfectly adequate as a big-budget, epic bit of wire-fu. Although, “perfectly adequate” feels like a disappointment, considering what I was hoping for, and this is not going to replace the 1998 film among my favorites, songs or no songs.

Dir: Niki Caro

Star: Yifei Liu, Li Gong, Jason Scott Lee, Donnie Yen

Matchless Mulan

By Jim McLennan★★★

“The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.”

I suppose this could be claimed to be a “mockbuster”, not so different from the sound-alike films released by The Asylum, e.g. Snakes on a Train. There’s no doubt this was made to ride the coat-tails of its far larger and better advertised big sister. And it’s not alone, with at least two other Chinese films apparently in production, one animated and the other live-action. But it’s a Chinese telling of a Chinese story, and as such, could also be considered as cultural reappropriation. We can’t really complain about them taking their legends back from the House of Mouse.

I suppose this could be claimed to be a “mockbuster”, not so different from the sound-alike films released by The Asylum, e.g. Snakes on a Train. There’s no doubt this was made to ride the coat-tails of its far larger and better advertised big sister. And it’s not alone, with at least two other Chinese films apparently in production, one animated and the other live-action. But it’s a Chinese telling of a Chinese story, and as such, could also be considered as cultural reappropriation. We can’t really complain about them taking their legends back from the House of Mouse.

Even in comparison to the tone of Disney’s live-action version, this plays as rather dark. There are throat-slittings, impalements and considerable quantities of arterial spray, certainly more brutal than the PG-13 violence in Mulan. However, Mulan (Xu) starts off as a bit of a pacifist. Her first encounter with the invading Rouran forces, comes when they’re out on patrol and suddenly stumble across the site of a massacre – it’s not unlike the similar scene in the animated version. When they come under attack by barbarian soldiers, she snaps off the head of her spear, so as to be able to engage them in non-lethal combat. Mulan later explains, “I came here to replace my father, not to take the lives of others. I don’t harm others and others don’t harm me.” Needless to say, this doesn’t quite sustain, and by the end, she’s impaling with the best of them.

Another difference is that two of her fellow villagers are assigned to the same post as Mulan – they know her secret, but respect it. This helps address one of the weaknesses in the live-action version, the lack of any real relationships for the heroine, because she’s forced to keep people at arm’s length. Instead, we get a real sense of her becoming part of a cohesive unit, such as her genuine distress when one of her brothers-in-arms is captured by the Rouran. That’s a contrast to the individual-first approach of Mulan, and there’s no magic to be found either, except for the wire fu used in the battle

Which actually brings me to my main complaint, the lack of interest the film has in these action sequences. While this is in line with the original story, which didn’t go into any great detail about her military exploits, it’s something we have come to expect. On occasion, things just kinda… drift off and fade to black, while the second half, which should build to a rousing finale, contains rather too much sitting about on the battlements of a lightly besieged fort, awaiting reinforcements. On the other hand, credit for not bothering to pussyfoot around the quagmire of politics. “The film is dedicated to the People’s Liberation Army of China”, boldly states the first end credit, clearly not giving a damn for Western (or Hong Kong) sensitivities on such topics. And that’s exactly how it should be.

Dir: Yi Lin

Star: Hu Xue Er, Wei Wei, Wu Jian Fei, Shang Tie Long

Kung Fu Mulan

By Jim McLennan★★★

“Disney gets some of their own medicine”

Going into this, I was expecting it to be really terrible. After all, this Chinese animated version seemed to be little more than a mockbuster, riding on the trails of Disney’s live-action version of the Mulan story. That is a little unfair, since this film began production back in 2015, five years before its Chinese release in October 2020. But it’s that timing – less than a month after Disney’s version came out – which inevitably invited comparison, and the local reaction was utterly scathing, despite an advertising tagline of “Real China, real Mulan.” It was compared unfavourably to a Western version of Chinese food, and lasted only three days in cinemas before being pulled, not taking in even one-tenth of its relatively small $15 million budget.

Going into this, I was expecting it to be really terrible. After all, this Chinese animated version seemed to be little more than a mockbuster, riding on the trails of Disney’s live-action version of the Mulan story. That is a little unfair, since this film began production back in 2015, five years before its Chinese release in October 2020. But it’s that timing – less than a month after Disney’s version came out – which inevitably invited comparison, and the local reaction was utterly scathing, despite an advertising tagline of “Real China, real Mulan.” It was compared unfavourably to a Western version of Chinese food, and lasted only three days in cinemas before being pulled, not taking in even one-tenth of its relatively small $15 million budget.

This is why I was braced for something at the level of pre-school stick figures. The reality, however, is nowhere near that bad. The animation is, it must be admitted, functional rather than impressive, but matters are helped significantly by decent voice acting and a plot which doesn’t appear tailored towards 12-year-olds. We join Mulan (Guest) already in progress, with her in the army and going on a mission to assassinate the prince of an invading army from the Northern grasslands, who are attacking the Central plains. Except, nobody mentioned there are two princes. She stumbles across the young one, and refuses to kill him.

While escaping, she ends up falling off a cliff with the older one, her actual target, Arke (Lee). As they make their way back to civilization, they fall for each other, partly because he conveniently forgets to mention the whole royalty thing. Needless to say, her superiors are not impressed with the failure to complete the mission. But there is a possibility of her marriage to Arke bringing peace between the two kingdoms, though there are some who are not in favour of that possibility either, and intend to use Mulan a pawn towards their own ends. I will say, there’s simply more plot going on here than in Disney’s version, and if the visual side is considerably plainer, the lack of ill-defined superpowers for its heroine is definitely a plus.

However, it doesn’t take advantage of the freedom which animation provides. While there are occasionally pretty moments, it falls short of capturing the majestic grandeur of China, and animated martial arts is always going to be less impressive than the live-action version. Though the dubbing is solid, with Guest in particular bringing her character to life, any cartoon version of Mulan is always going to end up being compared to Disney’s animated one, and this is just not as good. The main deficit here is the inability to make an emotional connection to the viewer. I never cared about the fate of Mulan or her country in the way I did while watching the classic edition. But considering my expectations going in, this was far better than I feared. Then again, I quite like the Western version of Chinese food. :)

Dir: Wallace Liao

Star (voice): Kim Mai Guest, Allan H. Lee, Vivian Lu, Greg Chun