★★★

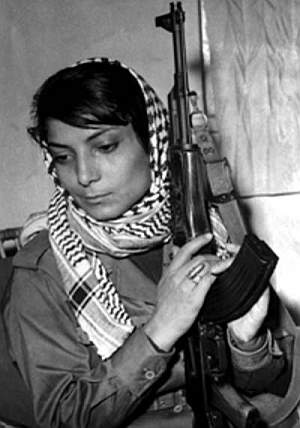

“Terrorist? Freedom fighter? You decide…”

Khaled became internationally famous in 1969, for hijacking a TWA flight from Rome to Athens, diverting it to Damascus, where it was blown up – after everyone had been taken off [this was a kinder, gentler era of terrorism]. She then underwent plastic surgery to conceal her identity, and the following year tried to hijack another plane. However, air marshals shot her colleague and captured Khaled, who was taken into custody in London, only to be released soon afterwards as part of a prisoner exchange. She returned to the Middle East, her sky-piracy career at an end, but became an icon of the Palestinian movement, and remains active in it to this day, despite travel restrictions. The Guardian wrote of Khaled in 2001,

Khaled became internationally famous in 1969, for hijacking a TWA flight from Rome to Athens, diverting it to Damascus, where it was blown up – after everyone had been taken off [this was a kinder, gentler era of terrorism]. She then underwent plastic surgery to conceal her identity, and the following year tried to hijack another plane. However, air marshals shot her colleague and captured Khaled, who was taken into custody in London, only to be released soon afterwards as part of a prisoner exchange. She returned to the Middle East, her sky-piracy career at an end, but became an icon of the Palestinian movement, and remains active in it to this day, despite travel restrictions. The Guardian wrote of Khaled in 2001,

She flamboyantly overcame the patriarchal restrictions of Arab society where women are traditionally subservient to their husbands, by taking an equal fighting role with men, by getting divorced and remarried, having children in her late 30s, and rejecting vanity by having her face reconstructed for her cause… “I no longer think it’s necessary to prove ourselves as women by imitating men,” she says. “I have learned that a woman can be a fighter, a freedom fighter, a political activist, and that she can fall in love, and be loved, she can be married, have children, be a mother.”

A fascinating and complex character, it can’t be said that much of the complexity – both hers, and the entire Middle East situation – comes across in this documentary, less than a hour long. You get a quick romp through her early history, her family’s departure from then-Palestine just after World War II, both hijackings, and then we leap forward to the present day, where she’s a mother and works for a political group. There are some interesting moments, such as where she draws a line between what she did, and the 9/11 hijackings: “I don’t agree with the murders of civilians, no matter where in the world”, and she’s been consistent in expressing that. More probing questions would have been welcome: instead, Makboul – brought up in Sweden by her Palestinian parents – admits to having been basically a fan. She interviews others involved in the hijacks, such as a stewardess and the crew, and follows Khaled on a trip to the Chatila refugee camp in the Lebanon, but the film ends abruptly, just as she asks Khaled about the negative image of Palestinians as terrorists that she helped create.

A fascinating and complex character, it can’t be said that much of the complexity – both hers, and the entire Middle East situation – comes across in this documentary, less than a hour long. You get a quick romp through her early history, her family’s departure from then-Palestine just after World War II, both hijackings, and then we leap forward to the present day, where she’s a mother and works for a political group. There are some interesting moments, such as where she draws a line between what she did, and the 9/11 hijackings: “I don’t agree with the murders of civilians, no matter where in the world”, and she’s been consistent in expressing that. More probing questions would have been welcome: instead, Makboul – brought up in Sweden by her Palestinian parents – admits to having been basically a fan. She interviews others involved in the hijacks, such as a stewardess and the crew, and follows Khaled on a trip to the Chatila refugee camp in the Lebanon, but the film ends abruptly, just as she asks Khaled about the negative image of Palestinians as terrorists that she helped create.

Overall, it’s a frustrating documentary, raising as many questions as it can be bothered to answer. It only scratches the surface of an icon from whom a line can be drawn to modern-day female ‘martyrs’ such as Wafa Idris, but leaves me eager to learn more: she wrote an autobiography, entitled My People Shall Live, published in 1973, so I may have to try and track that down. She certainly stands alongside Patty Hearst and Ulrike Meinhof in the ‘Hall of Fame’ for female terrorists; having had a song written about her by The Teardrop Explodes merits some extra cool points. But if you’re interested, here’s a probably better – less disjointed, certainly – interview with Khaled, carried out in 2000 by, ironically enough, the magazine Aviation Security. Leila notes the black humour there, saying she’s “looking forward to finding out what you wanted to know from me about the security of aviation…”

Dir: Lina Makboul

Aspiring teacher Catherine Ballou (Fonda), heads home to see her father in Wyoming, but finds him engaged in a struggle over his land with a land baron, and threatened by the villainous Tim Strawn (Marvin). She sends for legendary gun-fighter Kid Shelleen (also Marvin) to come protect them, only to find he is less legendary gun-fighter, and more alcoholic bum, incapable of saving himself. Strawn shoots Cat’s father and, when justice fails to be served, she heads off to a nearby outlaw town, where she vows to bring the land baron down and take revenge herself.

Aspiring teacher Catherine Ballou (Fonda), heads home to see her father in Wyoming, but finds him engaged in a struggle over his land with a land baron, and threatened by the villainous Tim Strawn (Marvin). She sends for legendary gun-fighter Kid Shelleen (also Marvin) to come protect them, only to find he is less legendary gun-fighter, and more alcoholic bum, incapable of saving himself. Strawn shoots Cat’s father and, when justice fails to be served, she heads off to a nearby outlaw town, where she vows to bring the land baron down and take revenge herself.