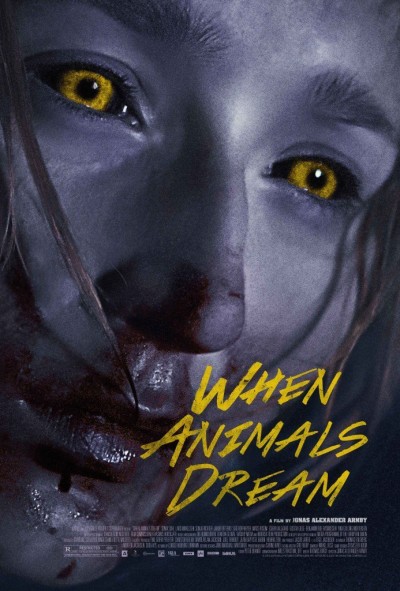

★★½

“Let the right lycanthrope in.”

If the vampire has been an equal-opportunity cinematic monster over the years, that’s less the case for the werewolf. Maybe it’s all the hair or the brutal strength, but from Underworld to Twilight, the ‘wolves have tended to be dogs rather than bitches – much though the latter might have been improved by a pack of ladies running around, like Taylor Lautner, with their tops permanently off. [I’d certainly have been on Team Jacobetta…] There are some exceptions – most notably the Ginger Snaps series, the first of which is among the best horror films of the 2000’s. This shares a similar theme, of a teenage girl who is disturbed by the changes in her body, which turn out to be more than just standard puberty. But the tone is rather more introspective, and to be honest, a good deal less successful.

If the vampire has been an equal-opportunity cinematic monster over the years, that’s less the case for the werewolf. Maybe it’s all the hair or the brutal strength, but from Underworld to Twilight, the ‘wolves have tended to be dogs rather than bitches – much though the latter might have been improved by a pack of ladies running around, like Taylor Lautner, with their tops permanently off. [I’d certainly have been on Team Jacobetta…] There are some exceptions – most notably the Ginger Snaps series, the first of which is among the best horror films of the 2000’s. This shares a similar theme, of a teenage girl who is disturbed by the changes in her body, which turn out to be more than just standard puberty. But the tone is rather more introspective, and to be honest, a good deal less successful.

The heroine here is Marie (Suhl) who has just started a job at the local fish-processing factory, when she starts to experience changes, both physical and mental. But it turns out not to be just Marie. Her mother (Richter), whose wheelchair-bound state Marie had always presumed was the result of a mundane illness, turns out to have the same affliction. After she had killed a local, her husband (Mikkelsen) had come to a pact with the local doctor, to prevent his wife from being… oh, dragged out of the house by a mob of angry villagers, wielding pitch-forks and torches, near enough. Her near-catatonic state is actually the result of a heavy regime of pharmaceuticals. And, now that Marie is beginning to exhibit the same symptoms, perhaps it’s time for her also to begin the same regimen. Or figure out an escape, with the help of her new boyfriend and co-worker, Daniel (Ottebro).

As the intro to this review hints, Arnby appears to be trying for a similar atmosphere to another Scandinavian monster mash, Let the Right One In. But too much of this comes over as flat and uninteresting, without enough development of the plot or characters. The performances are mostly good, Suhl underplaying things to the point of emotional deadness that’s actually entirely appropriate to the dead-end life into which she would otherwise be headed. It’s part of the point: her disease is also the cure for the disease of achingly tedious normality. Unfortunately, the movie spends too much grounded in that normality, and delivers on the aching tedium in full measure, mostly of slow and plodding. Arnsby eventually gets to the meaty stuff, with an impressive climax on board a ship at sea – nowhere to run, nowhere to hide – and if you’re in the right mood, looking for something more contemplative, this would perhaps hit the spot better. Unfortunately for the film’s grade, I was wanting something more traditionally horrific, and consequently found this to be no full-moon; probably a half-moon, at best.

Dir: Jonas Alexander Arnby

Star: Sonia Suhl, Lars Mikkelsen, Jakob Oftebro, Sonja Richter