Literary rating: ★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆

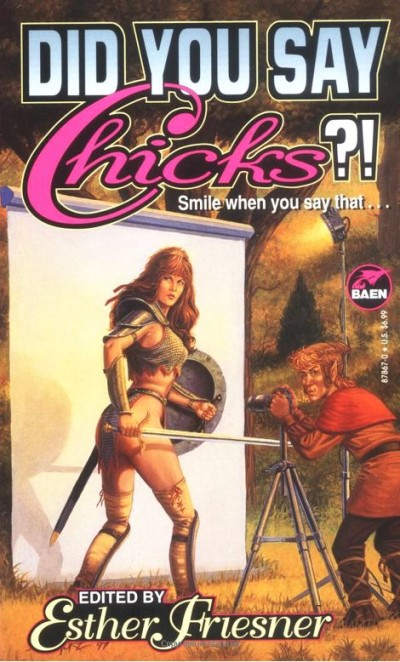

Published in 1998, this is the second of several installments in editor Friesner’s series of original-story anthologies featuring strong, mostly warrior women in (mostly) a sword-and-sorcery fantasy milieu. Marion Zimmer Bradley’s older, long-running Sword and Sorceress series is the closest counterpart, but the stories Friesner selects are much more often on the humorous side, and relatively lighter on actual violence –the protagonists here can handle themselves well in a fight, but tend in practice to triumph more by the use of intelligence, or to be able to find common ground with potential opponents where that’s possible. (Lethal violence is more apt to be mentioned, if at all, as an event that happened before the action in the particular story.) Many of my comments in my review of the first collection, Chicks in Chainmail, are relevant here, and my overall enjoyment was similar. (I rated both books at four stars.)

Published in 1998, this is the second of several installments in editor Friesner’s series of original-story anthologies featuring strong, mostly warrior women in (mostly) a sword-and-sorcery fantasy milieu. Marion Zimmer Bradley’s older, long-running Sword and Sorceress series is the closest counterpart, but the stories Friesner selects are much more often on the humorous side, and relatively lighter on actual violence –the protagonists here can handle themselves well in a fight, but tend in practice to triumph more by the use of intelligence, or to be able to find common ground with potential opponents where that’s possible. (Lethal violence is more apt to be mentioned, if at all, as an event that happened before the action in the particular story.) Many of my comments in my review of the first collection, Chicks in Chainmail, are relevant here, and my overall enjoyment was similar. (I rated both books at four stars.)

There are 19 stories here, written by 23 authors (three are two-person collaborations); as she did the first time, Friesner herself contributes a story, in addition to her role as editor. Eleven of these, including Harry Turtledove, Elizabeth Moon, Elizabeth Ann Scarborough, and Margaret Ball, also contributed to the 1995 first collection. Among the authors new to the series (and to me) here are Barbara Hambly, Sarah Zettel and S. M. Stirling. (Short biocritical endnotes are provided for all of the authors.) Besides her story, Friesner also prefaces the book with a dedicatory poem to Lucy Lawless, star of the then still-running Xena, Warrior Princess TV show. In keeping with the tone of most of the stories, her poetic style is more Ogden Nash than Dante, and she doesn’t take herself too seriously (after the poem, she appends a quote from Dr. Johnson, “Bad doggerel. No biscuit!”) –but there’s an underlying seriousness of equalitarian feminist message as well. (The final selection, Adam-Troy Castro’s “Yes, We Did Say Chicks!” is a similarly tongue-in-cheek flash fiction, but it’s cute!)

Not all of the stories are actual sword-and-sorcery, or fantasy. One of the two strictly serious ones, Turtledove’s “La Difference,” is a science-fiction yarn set on the Jovian moon Io, as a male-female pair of scientists trek across a dangerous and unforgiving alien terrain as they flee from enemy soldiers bent on slaughtering them. (This is also one where the female doesn’t singlehandedly save the day; she and her male partner work as a very good team.) Laura Anne Gilman’s “Don’t You Want to Be Beautiful?” is set in our own all-too-familiar world, where females are pressured by advertising and culture to fixate on their appearance and spend vast sums on products that supposedly enhance it; and it isn’t clear if the surreal aspects of the story are really happening or are the protagonist’s hallucinations. (This is one of a few stories that women readers will probably relate to more easily than men will.) Slue-Foot Sue, the heroine of Laura Frankos’ contribution, is the bride of Pecos Bill in the American tall-tale tradition, of which this story is definitely a continuation (though it’s also one of two stories that feature Baba Yaga, the witch figure from Russian folklore). And while the story is fantasy, the title character of Doranna Durgin’s “A Bitch in Time” isn’t a woman, but a female dog –albeit one who’s trained to detect and guard against magic.

My favorite story here is Hambly’s “A Night With the Girls,” the other strictly serious tale in the group. This features her female warrior series character, Starhawk, here on an adventure without her male companion Sun Wolf; I’d heard of these two before, but never read in that fictional corpus. (I’m definitely going to remedy that in the future!) Both Moon and Ball bring back their protagonists from their stories in the first book for another outing here, to good effect. The protagonist of Lawrence Watt-Evans’ “Keeping Up Appearances” is a professional hired assassin, who approaches her chosen line of work pretty matter-of-factly, without noticeable moral qualms. But she’s also capable of genuine love and loyalty, especially towards her business partner and common-law husband, with whom she hopes to one day settle down and retire.

So when she returns from a trip to find that he’s unilaterally accepted a contract on a powerful wizard and, while trying to scout the job by himself, gotten turned into a hamster, we can sympathize with her distress, and hope she can reverse the situation. (Can she? Sorry, no spoilers here!) If you’ve read Beowulf and want to know what really happened to Grendel, check out Friesner’s “A Big Hand for the Little Lady.” And Steven Piziks’ “A Quiet Knight’s Reading” is another tale that’s close to my heart (you’ll see why if you read it!). At the other end of the spectrum, two stories I didn’t especially care for were Scarborough’s “The Attack of the Avenging Virgins” and Mark Bourne’s “Like No Business I Know.” The former story, among other things, delivers an essentially sound message, but in a story so message driven that it’s more of a tract, and with an annoyingly “PC” vibe.

As with the original book, bad language is absent or minimal in most stories. Bourne’s is the exception, with quite a bit of it, including religious profanity and one use of the f-word. Sexual content is more noticeable in this volume, with unmarried sex acts (not explicit) in a couple of selections, rape of males by females in another, and a lesbian/bisexual theme thrown into another one as a surprise. “Oh Sweet Goodnight!” is the most frankly erotic story, with its focus on the heroine’s sex life; but the male-female author team treats sexual situations realistically rather than salaciously, and the ultimate message here isn’t as far from traditional morality as some might expect. (This is also a story where magic is absent; Fern’s a sword-toting guardswoman in a low-tech society, but she could just as easily be a divorced single mom in modern America, making a living as a cop or security guard –and modern readers will find her easy to relate to on that basis.)

Editor: Esther Friesner

Publisher: Baen, available through Amazon, currently only as a printed book

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.