★★

“More bomb than cherry.”

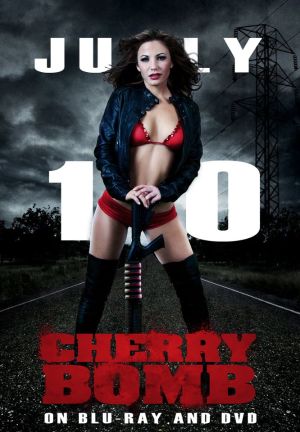

Cherry (Julin – yep, that appears to be her surname) is a stripper, whose life takes a turn for the worse when she is assaulted by five customers in a private room at the club where she works. The cops aren’t able to do anything, so she takes the law into her own hands, with the help of her brother (Rodriguez), who accidentally kills one of the perpetrators when he goes to demand help with Cherry’s medical bills – no prizes for guessing how that request goes. As the others realize someone is out to get them, and who that someone ins, they hire Bull (Hackley), a gigantic hitman, to stop Cherry before she gets to them.

Cherry (Julin – yep, that appears to be her surname) is a stripper, whose life takes a turn for the worse when she is assaulted by five customers in a private room at the club where she works. The cops aren’t able to do anything, so she takes the law into her own hands, with the help of her brother (Rodriguez), who accidentally kills one of the perpetrators when he goes to demand help with Cherry’s medical bills – no prizes for guessing how that request goes. As the others realize someone is out to get them, and who that someone ins, they hire Bull (Hackley), a gigantic hitman, to stop Cherry before she gets to them.

It’s clearly attempting to re-create the grindhouse era, but wimps out on most levels – for example, Cherry is a stripper who never shows any significant flesh. That’d perhaps be forgivable, if Julin’s performance hit the required notes elsewhere, but it wobbles uncertainly from giggly schoolgirl, incapable of forming any kind of plan to violated bitch, capable of ramming a vehicle into someone’s head (in probably the film’s most impressive moment). The other performances are similarly shaky, with the possible exception of Manning as the club owner, who captures the necessary tone for his role. Hackley is so shamelessly channeling Samuel L. Jackson from Pulp Fiction it goes beyond irritating into amusing – then past that, back into irritating again [Chris wondered if it was a white guy in blackface, it’s so clichéd!]. The action is equally as mixed a bag, swerving from well-staged to sloppy, occasionally even within

The overall impact is occasionally effective, with a couple of scenes that deliver the necessary wallop. But too often, it feels half-hearted, like they had a vague interest in resurrecting the grindhouse era, rather than a passion or drive, and it’s certainly all but lacking the “grind.” While I’m all in favour of emphasizing the “revenge” over the “rape” aspects of the story, the latter is so toned-down and muted – the assault itself is barely shown here – that the justification for the former is almost non-existent. That makes it difficult for the audience to get on board, when the ends don’t appear to justify the means.