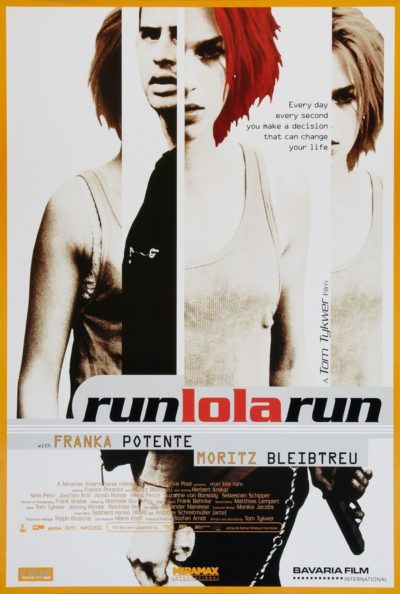

On August 20th, it will be twenty years since Run Lola Run – or as it was originally titled, Lola Rennt – was released in its native Germany. And, given the significance the number “20” has in the film, it seems appropriate to take a look back at it. Let’s be clear: this will not be a particularly critical analysis, more of an adoring reminiscence. For I love this film, and have since Chris first mailed me a bootleg copy (recorded in LP mode!) in 2000. I’d seen the poster outside an art-house cinema on Long Island, but knew little or nothing about it. Certainly, when I banged that VHS tape into the player, I had no clue I’d be watching a film which would become one of my all-time favourites.

Note: THERE WILL BE ENORMOUS SPOILERS BELOW THIS LINE

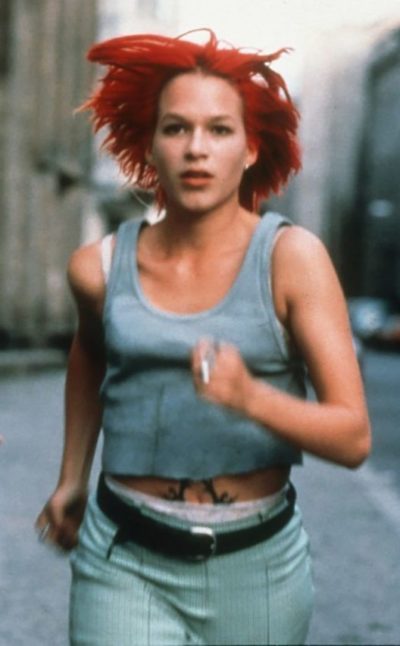

Why do I adore it? It’s amazingly rewatchable – we saw it in the cinema together for the first time a couple of months ago, at a 20th anniversary screening, and it was still near-perfect – perhaps because it works on so many levels. On one, it’s a simple action tale. Lola (Potente) has 20 minutes to come up with 100,000 Deutschmarks lost by her boyfriend, Manni (Bleibtreu), which belong to a crime boss. That, in itself, is a brilliant pitch for a thriller, and the first third unfolds in an incredibly stylish, yet straightforward way, as Lola runs across town, fails to convince her father (Knaup) to help, gets involved in Manni’s supermarket robbery… and then gunned down by a policeman in the subsequent stand-off.

Wait, what? We’re not half an hour in, and the title character is already bleeding out on a Berlin street? How the hell is Tykwer going to sustain this? And this is where the film pulls of its master stroke, which is breathtaking in its audacity. After a brief interlude of Lola and Manni lying in bed, the film simply resets. It goes back to the point where Lola left her apartment, and the story unfolds again. However, this time, we are introduced to another of the film’s main themes: chaos theory. A tiny change in initial circumstance has a knock-on effect – there’s a pointed shot of dominoes toppling – and leads us to a completely different conclusion.

It’s still not what Lola wants. And, as the old song goes, whatever Lola wants, Lola gets. So we reset once more, with a further slight tweak at the beginning, subsequently causing the dominoes to fall in another, radically different way. [The moment when you figure out what’s going on is perhaps the greatest “Holy shit!” moment I’ve ever had in my film-viewing career] This time, she not only raises the money, Manni recovers his as well, and the pair wander off. Happy ever after? Hard to say. The enigmatic look on Lola’s face when he asks her, “What’s in the bag?” suggests her hard-won ending and new-found skill-set might have broadened her horizons, beyond the slightly shady and scatterbrained current boyfriend.

It’s still not what Lola wants. And, as the old song goes, whatever Lola wants, Lola gets. So we reset once more, with a further slight tweak at the beginning, subsequently causing the dominoes to fall in another, radically different way. [The moment when you figure out what’s going on is perhaps the greatest “Holy shit!” moment I’ve ever had in my film-viewing career] This time, she not only raises the money, Manni recovers his as well, and the pair wander off. Happy ever after? Hard to say. The enigmatic look on Lola’s face when he asks her, “What’s in the bag?” suggests her hard-won ending and new-found skill-set might have broadened her horizons, beyond the slightly shady and scatterbrained current boyfriend.

It can be enjoyed simply on that level: a demonstration of how a tiny change at the right point can have an extraordinary effect. This impact isn’t limited to Lola. Throughout the film, as her path crosses with various other people, we see what happens to them in this version of the future, through a series of still photos preceded by an “And then…” caption. It’s another brilliant idea, conveying an entire story in a few seconds. Like so much in the film, there’s absolutely no fat. Tykwer can’t afford that: the entire film runs only 80 minutes, and has to tell three similar, yet divergent story-lines, so time is, literally, of the essence here. The film and its heroine, must keep moving forward.

As a purely kinetic spectacle, it’s great, powered in part by the pulsing techno soundtrack, crafted by Tykwer along with Johnny Klimek and Reinhold Heil. They had previously collaborated for the music on Tykwer’s second feature, Winter Sleepers, and hit the ball out of the park with this collection of electronica. There are only two movie soundtracks which I’ll listen to on a standalone basis: this and Bollywood comedy, Singh Is Kinng. With lyrical work by Potente, it’s no less ceaselessly in motion than the movie – except for one scene which flips the script, going into slo-mo as it crashes into the sultry jazz tones of Dinah Washington. “What a difference a day makes,” she tells us. What a difference, indeed.

But it’s only when you dive deeper you realize the film has layers, with aspects deliberately left open to the viewer’s interpretation. It sets its philosophical stall out early, opening with quotes on the cyclical nature of life from poet T.S. Eliot… and German football coach, Sepp Herberger. “After the game is before the game,” says the latter; or in the context of the film, after Lola’s run is before her run. There’s a voice-over, by Hans Paetsch (well-known in Germany as, appropriately, a narrator of fairy-tales), who poses a set of philosophical queries before revealing their semi-pointlessness since these are, “questions in search of an answer, an answer that will give rise to a new question, and the next answer will give rise to the next question and so on.”

Then it’s game on. Right from the start, it appears that Lola has “a very particular set of skills”. At the end of her conversation with Manni, she throws the phone into the air, only for it to land, neatly on the base. This is… not normal. There’s also her scream, which can shatter glass and perhaps alter the outcome of a roulette wheel: it’s her method to “take control of the chaos” which is threatening to overwhelm her life. And that’s not even getting into her ability to rewind time, and get a “do over”, a power which may be driven by her intense love for Manni, and refusal to accept being separated from him. I hypothesize that she may be a goddess of some kind, slumming it in the body of a young German punkette. It’s as valid a theory as any the film provides.

Nowhere is Lola’s dominance over petty reality more obvious than in the casino. She doesn’t have enough money to buy a chip, yet the cashier gives her one anyway. Her clothes are clearly at odds with the casino’s dress code, yet she’s allowed to take part. And when she’s about to be ejected after her first win, she turns to the employee, stares levelly at him and says “Just one more game.” This is not a request, or even a demand. It’s a statement of fact, utterly undeniable. There will be one more game. What happens subsequently is further proof that what we perceive as chance is Lola’s tool, and not the other way round.

Yet in that light, it’s worth noting she’s not immune to external forces. Indeed, the first domino is her descent of the staircase in her apartment block and an encounter with another resident and his dog. The resulting outcome begins the process of changing the timeline. These are also not complete “resets”. In the opening run, Manni has to show her how to operate the safety on a gun; in the second, she knows what to do. Nor is her power without limits, or Lola could simply go back and prevent her boyfriend from losing the money to begin with. There are, apparently, rules to this game, though who sets them and why, is not a topic addressed in the film.

Yet in that light, it’s worth noting she’s not immune to external forces. Indeed, the first domino is her descent of the staircase in her apartment block and an encounter with another resident and his dog. The resulting outcome begins the process of changing the timeline. These are also not complete “resets”. In the opening run, Manni has to show her how to operate the safety on a gun; in the second, she knows what to do. Nor is her power without limits, or Lola could simply go back and prevent her boyfriend from losing the money to begin with. There are, apparently, rules to this game, though who sets them and why, is not a topic addressed in the film.

I love the use Tykwer makes of colour in the film, in particular red, yellow and green [likely not by coincidence, the same ones used in traffic lights]. Once you’re primed to look for their use, you’ll see them appearing, over and over again. Interpreting their meaning is trickier; it’s not something the director appears to have addressed, even on the DVD commentary. Red is clearly the dominant shade, from Lola’s hair to the filters applied to the scenes between runs, where she and Manny are lying in bed. While often associated with danger, it is also a colour associated with love and passion, and both are highly significant elements here.

Meanwhile, Manny is linked to yellow, most obviously in his dyed hair, and the phone booth in and around which he spends much of his time. At a guess, I’d says this symbolizes his life grinding to a halt, Manny’s anxiety and subsequent inaction (particularly in comparison to Lola) and perhaps the cowardice of his refusal to ‘fess up to his boss and face the consequences of his incompetence. Also of note: the scenes in which the pair do not appear are, quite deliberately, shot on noticeably lower-quality stock than scenes with Lola and Manny: Tykwer said he wanted those scenes to seem less “real”.

Something else which shows up repeatedly are spirals: the staircase down which Lola runs, the bar outside which is Manni’s phone-box; even the slow descent into entropy of the ball on the roulette wheel. This seems to have been inspired by Tykwer’s love of Vertigo, something explicitly referenced in the casino. There, the mysterious painting on the wall, of the back of a woman, is a portrait of Kim Novak in the gallery from Hitchcock’s movie, whipped up in 15 minutes and from vague memory by the art director, to fill an annoying blank space on the wall. [It went on to hang in the director’s living-room!]

Chris and I love the film so much, that when we went to Berlin on honeymoon, one of the things we did was spend an afternoon visiting as many of the locations as possible. We discovered the film does play fast and loose with local geography. The settings are situated well beyond the capabilities of even an Olympic athlete to cover in 20 minutes, so we were not able to get to the supermarket, for instance. I do, however, still have pics of Chris “running” outside the bank (which is now the Hotel de Rome, with rooms starting at $300 per night…)

Though not the first feature for either Tykwer or Potente, this has become the one by which both are defined. Such is our love for Run Lola Run, we’ll pretty much watch anything they’re involved with, even though nothing has come close to matching it. Probably wisely, Tykwer hasn’t tried, even when re-uniting with his lead actress and soundtrack composers for The Princess and the Warrior. While their other works have certainly had their merits, it feels like this was the cinematic equivalent of catching lightning in a bottle. Small enough for the director to be allowed artistic control, yet large enough to be able to deliver it, it’s a film which is every bit as fresh and invigorating now as it was in 1998.

The upcoming Chinese remake, announced last year, will have some very large, black boots to fill…