Professional wrestling is perhaps more international than you’d expect. While traditional territories – USA, Japan, Mexico and the UK – still remain the powerhouses, there is hardly a country in the world without its own local pro federation. But even I had not heard of Ecuador’s cholita luchadoras. Cholita is a term used for the native women there, usually found at the bottom of the social pyramid, both in terms of wealth and education. So the term translates as the “fighting cholitas“, who use pro wrestling as a way out of poverty, and to help them at least approach the average wage there, which is around $270 per month.

Professional wrestling is perhaps more international than you’d expect. While traditional territories – USA, Japan, Mexico and the UK – still remain the powerhouses, there is hardly a country in the world without its own local pro federation. But even I had not heard of Ecuador’s cholita luchadoras. Cholita is a term used for the native women there, usually found at the bottom of the social pyramid, both in terms of wealth and education. So the term translates as the “fighting cholitas“, who use pro wrestling as a way out of poverty, and to help them at least approach the average wage there, which is around $270 per month.

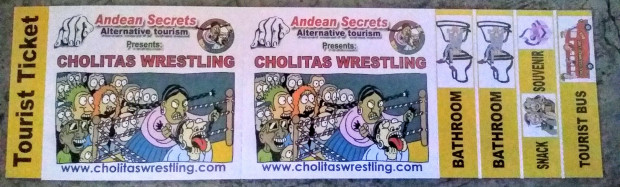

While initially intended purely for local consumption, it has achieved renown, both local and internationally, and become a tourist attraction. Local company “Andean Secrets” – run by one of the cholitas – runs excursions that pick visitors up at their hotel and take them to one of their shows at the Multifunctional Centre in El Alto. Tourists have to pay five times the cost for locals, but the price does get them ringside seats. In style, it’s closest to Mexican lucha libre, with the good girls (technicos) going up against the rudos, who cheat. abuse the audience and collude with a corrupt referee to try and achieve victory. You can generally tell who’s who from the names they choose. There’s an almost standard format to these: Chela la Maldita, Sonia La Simpática, Juanita La Cariñosa (Affectionate), Rosita La Rompecorazones (Heartbreaker) or Silvina La Poderosa (Powerful).

An exception is the matriarch of the cholitas, known as Carmen Rosa. She was part of the original group of cholitas and one of the three who made it through the training program. She said, “For me, wrestling is my life; it is in my heart. It makes it hard for me to choose between wrestling and my family. They have asked me to stop fighting and sometimes I think about quitting, but I can’t. My heart beats fast at the mere mention of wrestling, or when I go to see a show, not to mention when I am about to enter the ring. There is nothing I love more than wrestling.” But even after a decade, she’s not fully professional: her day job is running her family’s local snack-bar.

That’s par for the course – as another example, Benita La Intocable (the Untouchable, one of the most high-flying of the cholitas) was training to be a nurse. Because the pay received is still peanuts by Western standards – typically no more than thirty dollars for their night’s work – but it’s an improvement on the very limited opportunities available to cholitas, typically as maid or other menial work. For until recently, the indigenous men and women had suffered a long history of discrimination, denied education, health care and public presence. The election in 2006 of the first Bolivian President from their group, Evo Morales, has helped address things, but there’s a reason the cholitas fight in El Alto, not the more prosperous La Paz.

That’s par for the course – as another example, Benita La Intocable (the Untouchable, one of the most high-flying of the cholitas) was training to be a nurse. Because the pay received is still peanuts by Western standards – typically no more than thirty dollars for their night’s work – but it’s an improvement on the very limited opportunities available to cholitas, typically as maid or other menial work. For until recently, the indigenous men and women had suffered a long history of discrimination, denied education, health care and public presence. The election in 2006 of the first Bolivian President from their group, Evo Morales, has helped address things, but there’s a reason the cholitas fight in El Alto, not the more prosperous La Paz.

They first entered the ring around the start of the millennium, the idea of local promoter Juan Mamani. Initially intended purely as a gimmick during a period of audience decline – he also considered using midgets – it took off in an unexpected way, with over fifty women showing up for that first open try-out. But after years under Mamani’s thumb, in which the women took the risks, and the associated damage, while his promotion, Titanes del Ring (Titans of the Ring) took the profits, there was a schism. Carmen and others among his top wrestlers left in 2011, starting up their own independent association, Diosas del Ring (Goddesses of the Ring), to gain the fruits of their own efforts. [Mamani allegedly then hired another woman, to play what I guess was Carmen Rosa v2.0!]

It was initially a struggle, with the women struggling to find even a place to train, and some of the defectors subsequently returning to Mamani – a man whom National Geographic once described as “a tall, angular man whom it would be kind to call unfriendly”. But Carmen and her colleagues persisted, and now they’ll get close to a thousand people attending their weekly events. She has become a celebrity, and not just in El Alto or even Bolivia. Carmen has traveled widely as a result, including trip to America and Peru, as well as being brought to London for 2015’s ‘Greatest Spectacle of Lucha Libre’ festival at York Hall.

The most immediate difference any wrestling fan will notice, is the costumes. While in America, wrestlers typically wear a limited amount of tight-fitting clothing, intended not to interfere with their moves, the cholitas come to fight in the traditional native costumes, consisting of multiple layered skirts (typically five or six), and little bowler hats which perch on top of their long, braided hair. [Bonus fact: the angle of the hat indicates marital status] It seems implausible they would be able to do anything requiring significant movement, but you’d be surprised. Also worth noting: the women need particular endurance, due to the altitude. Bolivia’s capital, La Paz, is the highest in the world, and the nearby low-income suburb of El Alto, home of the cholitas, is more elevated still, at over 13,500 feet above sea-level. Simply breathing is hard work, that far up.

The most immediate difference any wrestling fan will notice, is the costumes. While in America, wrestlers typically wear a limited amount of tight-fitting clothing, intended not to interfere with their moves, the cholitas come to fight in the traditional native costumes, consisting of multiple layered skirts (typically five or six), and little bowler hats which perch on top of their long, braided hair. [Bonus fact: the angle of the hat indicates marital status] It seems implausible they would be able to do anything requiring significant movement, but you’d be surprised. Also worth noting: the women need particular endurance, due to the altitude. Bolivia’s capital, La Paz, is the highest in the world, and the nearby low-income suburb of El Alto, home of the cholitas, is more elevated still, at over 13,500 feet above sea-level. Simply breathing is hard work, that far up.

The matches are not limited to women vs. women, with the cholitas taking on their male counterparts, as dictated by the storyline. It’s a one of a kind breed of professional wrestling, and a take which goes beyond the first impression of the unique style. For it is sports entertainment, not just based on athletic talent combined with the struggle of “good against evil,” but a version which offers social and political commentary too. Below, you’ll find a playlist of Youtube videos, including both documentaries and other clips, which give a bit more insight into the world of the fighting cholitas.

“Sometimes my daughters ask why I insist on doing this. It’s dangerous; we have many injuries, and my daughters complain that wrestling does not bring any money into the household. But I need to improve every day. Not for myself, for Veraluz, but for the triumph of Yolanda, an artist who owes herself to her public.”

— Yolanda La Amorosa