This article was inspired by my mild irritation at documentary film Fly Like a Girl which, while a worthy item, was almost exclusively American-focused. You could have watched it all the way through, and come to the conclusion that Americans not only invented flight, they were the only ones to take to the air over the following century. That isn’t the case. Names like Jean Batten (New Zealand), Nancy Bird Walton (Australia), Hélène Dutrieu (Belgium) or Beryl Markham (Britain), all deserve recognition for their pioneering roles, rather than it being just Amelia Earhart. Which brings us to Amy Johnson who, both in life and death, was not all that dissimilar from “Lady Lindy”: shattering the glass ceiling for female aviators, breaking records and achieving huge national fame, before disappearing in a plane accident, with neither woman’s body being recovered.

This article was inspired by my mild irritation at documentary film Fly Like a Girl which, while a worthy item, was almost exclusively American-focused. You could have watched it all the way through, and come to the conclusion that Americans not only invented flight, they were the only ones to take to the air over the following century. That isn’t the case. Names like Jean Batten (New Zealand), Nancy Bird Walton (Australia), Hélène Dutrieu (Belgium) or Beryl Markham (Britain), all deserve recognition for their pioneering roles, rather than it being just Amelia Earhart. Which brings us to Amy Johnson who, both in life and death, was not all that dissimilar from “Lady Lindy”: shattering the glass ceiling for female aviators, breaking records and achieving huge national fame, before disappearing in a plane accident, with neither woman’s body being recovered.

It was a different era in which Earhart and Johnson operated: the world was still being explored, with many feats remaining to be accomplished. It was only in 1927 that the first solo trans-Atlantic flight occurred, and society was eager for similar examples of derring-do. Amy had grown up in a comfortably middle-class home in the North of England, going to university, but was unable to find a career that satisfied her. But she loved to fly, initially as a pastime, but with increasing fervour, getting her pilot’s license in 1929, and also becoming the first British woman with a ground engineer’s license. She began planning to be the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia, hoping to beat the existing record for the trip, Bert Hinkler’s 15½ days. It was a journey of 11,000 miles, despite her longest flight to this point being just a couple of hundred, from London to the family home in Hull.

The necessary financial backing proved hard to obtain, but she eventually raised the necessary funds with the help of her father, plus oil tycoon and aviation supporter Lord Wakefield, founder of the company which would became Castrol Oil. On May 5th, 1930, she took off from Croydon Airport, with little fanfare or attention. Among her equipment were a revolver, to fend off bandits, and a letter offering to pay a ransom – presumably if the revolver didn’t work. However, brigands proved not the biggest danger she’d encounter. She was forced down in the desert by a sandstorm as she approached Baghdad, with her plane stalling out twice. “I had never been so frightened in my life,” she said of the experience.

Repeated mechanical problems, many of which were caused by the repeated failure of an undercarriage strut, also threatened to derail Johnson’s attempt. But with good fortune and innovative thinking, she was able to continue. Perhaps the greatest example came in Burma, after she ripped up her wing in a rough landing, with no replacement cloth to hand. However, after the First World War, a stock of airplane fabric had been left behind, and recycled into shirts by the local women. Amy was able to re-recycle the shirts back into the necessary material to complete repairs and carry on. By now, word of her exploits was spreading, and she began to be feted on her arrival at each stop. Back in Britain, too, the papers began to report on her exploits, and got into competition for the rights to Amy’s story. The Daily Mail won, with a bid of two thousand pounds.

On May 24, she landed in the northern Australian city of Darwin. Johnson had not beaten the record, taking 19½ days for her flight, but had captured the public’s imagination and interest, in a way few women of the time managed to do. A six-week tour of Australia followed, during which she met her future husband, James Mollison, for the first time. She was equally celebrated on a slower, less arduous journey back to Britain, finally returning to Croydon on August 4. Although Johnson dutifully put up with all the banquets and speeches, she was never comfortable with her fame or the adulation, later saying, “I hated all the theatres, cinemas, first nights, and parties. It’s an unnatural and artificial life. I’m glad those days are over.”

The flight remained Amy’s defining moment, though it was far from her only, or even most successful, adventure. After marrying Mollison in 1931, she promptly broke his record for the solo flight from London to Cape Town, South Africa at just under four days and seven hours. With co-pilot C.S. Humphrey, she also set the UK-Japan mark, flying seven thousand miles in ten days. Finally, in May 1936, she reclaimed the Cape Town record, with a flight of three days, six hours and 26 minutes. But Amy simply lived to fly, regardless of the distance. The disappearance of her friend Amelia Earhart in 1937, did dampen her enthusiasm somewhat, though she found a new passion for unpowered flight, taking up gliding and appreciating the tranquility it offered.

World War II broke out in 1939, and Amy wanted to do her part. While Britain would not let women join their air force (unlike the Russians ended up allowing), they were allowed to be part of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). Their duties included moving planes around the country as needed, such as from the factory to the air fields from which they would operate. Amy signed up, receiving a salary of six pounds per week. But on January 5, 1941 – two years to the day after Earhart was officially pronounced dead – Amy took her final flight. It appears she lost her way in fog, on a flight from Blackpool to Oxfordshire, and bailed out of her plane, but landed in the River Thames and drowned. Her body was never recovered, but she remains a heroic figure, representing courage, perseverance, dedication and humility in equal measure.

Below are a selection of film clips documenting her life and death, including sections of 1932 short Dual Control, which featured both Johnson and her than husband, Jim Mollison.

There have been two feature films based on Johnson’s life, made over 40 years apart, and interesting as much for their differences as anything else. Below, you’ll find reviews of both movies.

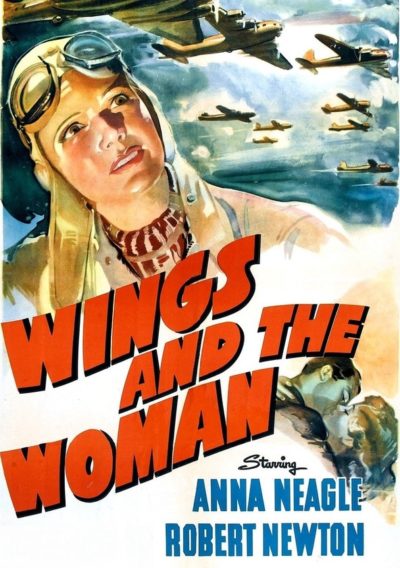

They Flew Alone

By Jim McLennan★★½

“Puts the plain in aeroplane.”

This bio-pic of aviator Amy Johnson appeared in British cinemas a scant eighteen months after she disappeared over the River Thames. That put its release squarely in the middle of World War II, and explains its nature which, in the later stages, could certainly be called propaganda. There’s not many other ways to explain pointed lines like “Our great sailors won the freedom of the seas. And it’s up to us to win the freedom of the skies. This is first said during a speech given by Johnson in Australia, then repeated at the end, over a rousing montage of military marching and flying. I almost expected it to end with, “Do you want to know more?”

This bio-pic of aviator Amy Johnson appeared in British cinemas a scant eighteen months after she disappeared over the River Thames. That put its release squarely in the middle of World War II, and explains its nature which, in the later stages, could certainly be called propaganda. There’s not many other ways to explain pointed lines like “Our great sailors won the freedom of the seas. And it’s up to us to win the freedom of the skies. This is first said during a speech given by Johnson in Australia, then repeated at the end, over a rousing montage of military marching and flying. I almost expected it to end with, “Do you want to know more?”

From the start, the film does a decent job of depicting Johnson (Neagle) as a likable heroine, who refuses to bow to convention – she’s first seen rebelling against the straw hat that’s part of her school uniform. We then follow her through university, though the degree apparently only qualifies her for jobs in a haberdashery or as a secretary (must have been a gender studies…). Unhappy with these dead-end occupations, she takes up flying, earning her pilot’s license and buying her own plane. It’s about here that the film really hits trouble, because director Wilson has no idea of how to convey the thrill of free flight. Endless series of newspaper headlines, ticker tapes and cheering crowds is about all we get, along with obvious rear-projection shots of Amy looking slightly concerned in the cockpit.

It’s almost a relief when the romance kicks in, represented by fellow pilot Jim Mollison (Newtron), who woos Amy while looking to set flight records of his own. Problem is, he’s a bit of a dick: quite why Amy falls for him is never clear. It’s clearly a mistake, with his drinking, womanising (or as close as they could depict in the forties!) and resentment at her greater fame and desire for independence eventually dooming the marriage – in another of those newspaper headlines. However, there is one decent sequence, when the husband and wife fly as a pair from Britain to America, largely through dense fog. This is edited nicely and, in contrast to all other flights, does generate some tension.

The bland approach includes Johnson’s final mission, depicted here as her running out of fuel while seeking somewhere to land in fog, bailing out, and drowning in the river. Cue the montage mentioned above, though the film does redeem itself with a final caption, worth repeating in full. “To all the Amy Johnsons of today, who have fought and won the battle of the straw hat – who have driven through centuries of convention – who have abandoned the slogan ‘safety first’ in their fight for freedom from fear – from want – from persecution – we dedicate this film.” It’s an honourable thought, considerably deeper and more well-executed than something which generally feels like it was rushed out, without much effort put into it.

Dir: Herbert Wilcox

Star: Anna Neagle, Robert Newton, Edward Chapman, Joan Kemp-Welch

a.k.a. Wings and the Woman

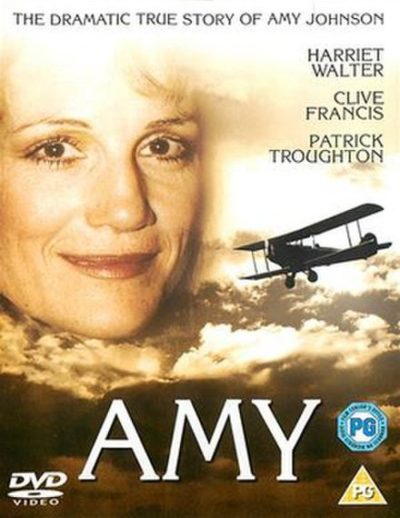

Amy

By Jim McLennan★★★

“What rules?”

It’s interesting to compare the approach taken in this biopic of aviation heroine Amy Johnson, made in 1984, with the one over 40 years earlier (and shortly after her death) in They Flew Alone, and note the similarities and differences. Both are relatively restrained in budget. The earlier one because it was a low-cost production, made during a war; the later one because it was made for television – and the BBC at that, never a broadcaster known for its profligate spending! As a result, both are limited in terms of the spectacle they can offer, and end up opting to concentrate on Amy as a character. It’s the cheaper approach.

It’s interesting to compare the approach taken in this biopic of aviation heroine Amy Johnson, made in 1984, with the one over 40 years earlier (and shortly after her death) in They Flew Alone, and note the similarities and differences. Both are relatively restrained in budget. The earlier one because it was a low-cost production, made during a war; the later one because it was made for television – and the BBC at that, never a broadcaster known for its profligate spending! As a result, both are limited in terms of the spectacle they can offer, and end up opting to concentrate on Amy as a character. It’s the cheaper approach.

This benefits from a little more distance, and doesn’t need to paint an almost beatific picture of its subject for patriotic propaganda purposes. It begins with Amy (Walter) already fully grown up and seeking to raise funds for her record-setting flight to Australia, despite only a hundred hours of solo experience. Actually, 102, as she points out to a potential sponsor, also delivering the line above. when it’s pointed out she’s not even supposed to be in the hangar. The film does a somewhat better job of capturing Amy in flight, with wing-mounted camerawork that’s an improvement over the obvious rear-projection used in Alone. Yet there’s still too much reliance on newspaper headlines, to avoid having to spend money, though there is some deft use, of what’s either genuine newsreel footage or artfully re-created, sepia facsimiles.

There is a similar focus on her failed marriage to fellow aviator, Jim Mollinson (Francis, who really does not sound Scottish at all), and he doesn’t come off much better than the character did in Alone. Jim is portrayed again as a drunken womanizer, though this version plays down the idea of him becoming fed-up at being overshadowed by Johnson’s exploits. It feels like there’s a slight hint of a romantic relationship between Johnson and earlier co-pilot Jack Humphreys (Pugh). There’s also a statement that she had an operation to prevent her from having children, which I had not heard before. But it does depict Amy as quickly becoming fed up with the endless appearances required by her Daily Mail contract post-Australia flight, which seems accurate: she was happier out of the public eye.

The biggest difference between the two films is probably the way they depict her death. This… simply doesn’t. It ends instead, in a 1940 meeting with her ex-husband, while they were both ferrying planes around Britain for the Air Transport Auxiliary. Barbs are traded, and Jim seems annoyed when a fan comes up seeking Amy’s autograph and ignoring him completely. She leaves for her flight, despite being told regulations won’t let her take off due to the conditions. “What rules?” she says, before a caption details her death in 1941. It’s understated, and that’s in line with the approach taken here – perhaps too much so. While I think it is slightly better than Alone, this feels mostly due to better technical aspects. I still can’t feel either film gave me a true understanding of what she was like, or what made her tick.

Dir: Nat Crosby

Star: Harriet Walter, Clive Francis, George A. Cooper, Robert Pugh