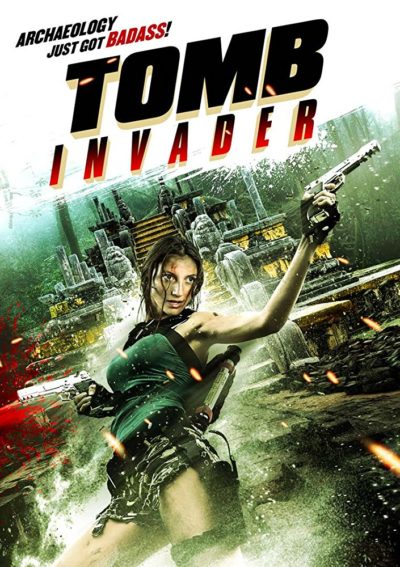

★½

“Deserves to be buried.”

Anyone can review Tomb Raider. Here, we go the extra mile and review the third-rate knock-off version. For despite being someone whose fondness for maverick studio The Asylum is already on the record, even I have to admit this one is not at all good. It’s one of their “mockbusters”, clearly designed to cash in on the Tomb Raider reboot, and I can see some potential ways how this could have worked. For example, hire a real athlete – ideally Jessie Graff, but probably someone cheaper from the parkour field – and make a no-frills but CGI-free version, with a heroine actually doing impressive things in the running, jumping and climbing department. [Call me, David Michael Latt! Let’s talk…] Instead, we get a cast of four, walking around a forest for 80 minutes and bickering at each other, book-ended by five minutes of somewhat interesting action.

Anyone can review Tomb Raider. Here, we go the extra mile and review the third-rate knock-off version. For despite being someone whose fondness for maverick studio The Asylum is already on the record, even I have to admit this one is not at all good. It’s one of their “mockbusters”, clearly designed to cash in on the Tomb Raider reboot, and I can see some potential ways how this could have worked. For example, hire a real athlete – ideally Jessie Graff, but probably someone cheaper from the parkour field – and make a no-frills but CGI-free version, with a heroine actually doing impressive things in the running, jumping and climbing department. [Call me, David Michael Latt! Let’s talk…] Instead, we get a cast of four, walking around a forest for 80 minutes and bickering at each other, book-ended by five minutes of somewhat interesting action.

This is, however, as much a rip-off of Indiana Jones as Tomb Raider, right from a heroine called Ally (Vitori), as in short for “Alabama”, who lectures in archaeology at a university. There’s an early scene involving escape while being chased by a rolling stone, differentiated largely by the presence of spikes on it. Hmm. The main plot concerns the search for an artifact called the Heart of the Dragon, which Ally’s mother died looking for in China, twenty years previously. When the late mother’s journal resurfaces, Ally is drawn back to China – or, at least, stock footage thereof, before cutting to the non-Chinese forest – by billionaire Tim Parker (Sloan). He has hired Ally’s rival, Nathan (Katers), and the difference in tomb raiding, sorry, invading philosophy is what leads to the bickering mentioned above.

The lack of energy here is likely the most painful element. Our explorers go through the forest at approximately the speed you would escort an elderly relative around a botanical garden, and when they eventually reach the artifact site, and further booby-traps are unleashed, there no sense of urgency to escape. Even after one of the team is taken down, it’s entirely lacking in emotional impact, partly because the victim served little or no purpose to that point, and partly because they were painfully annoying whenever they opened their mouth. The “real” original movies, particularly the second entry, were no great shakes, yet they look like classics put next to this pale and weak imitation.

Vitori does occasionally look the part, and the minimal amount of action she gets to do is not poorly handled. I did like the sequence where a terracotta statue came to life and had to be fought: it’s exactly the kind of thing I expected to see from this. The film needs about sixty more minutes like it, rather than the jaw-jacking in the woods we actually get. Though considering this was likely made for less than the budget devoted to the care and nurture of Alicia Vikander’s eyebrows, I guess we should be grateful for whatever we get.

Dir: James Thomas

Star: Gina Vitori, Evan Sloan, Samantha Bowling, Andrew J Katers

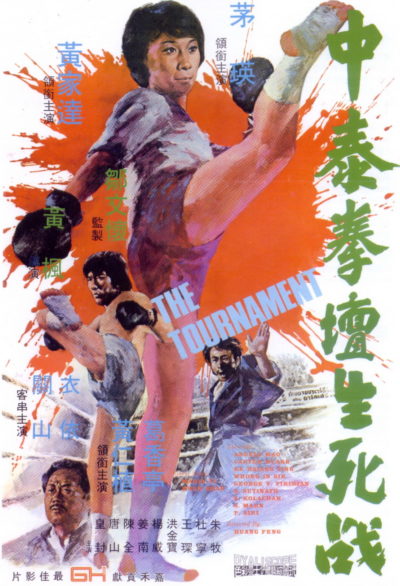

There’s a lot of chit-chat about face, honour and respect here. It begins when the master of a kung-fu school, Lau, has his daughter kidnapped by local hoodlums, after he won’t cough up protection money. Perhaps surprisingly, rather than using his skills to kick their arses, he sends two students to Thailand, including his son, Hong (Wong) in an effort to win the necessary funds. Hong loses, the other student is killed, and Lau is drummed out of the local Kung-Fu Association for having disgraced the name of Chinese martial arts by losing to foreigners. He’s so devastated, he hangs himself, leaving it up to his daughter, Siu Fung (Mao) to restore the family name, learn how to mesh Chinese kung-fu with Thai boxing, and rescue her sister. Quite the “to-do” list, I’d say.

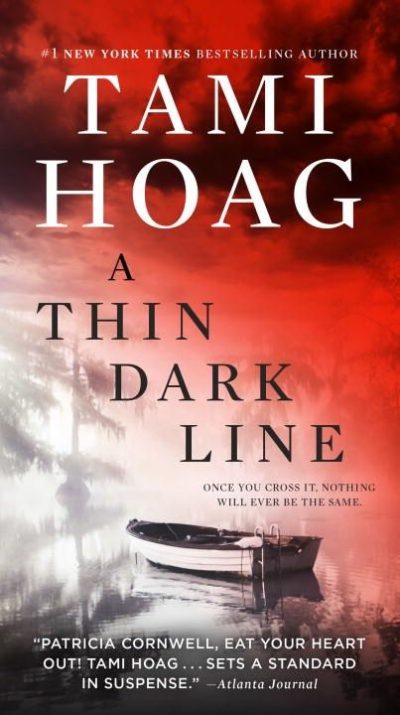

There’s a lot of chit-chat about face, honour and respect here. It begins when the master of a kung-fu school, Lau, has his daughter kidnapped by local hoodlums, after he won’t cough up protection money. Perhaps surprisingly, rather than using his skills to kick their arses, he sends two students to Thailand, including his son, Hong (Wong) in an effort to win the necessary funds. Hong loses, the other student is killed, and Lau is drummed out of the local Kung-Fu Association for having disgraced the name of Chinese martial arts by losing to foreigners. He’s so devastated, he hangs himself, leaving it up to his daughter, Siu Fung (Mao) to restore the family name, learn how to mesh Chinese kung-fu with Thai boxing, and rescue her sister. Quite the “to-do” list, I’d say. This is officially characterized (though not in the cover copy) as the fourth book of the author’s Doucet series. However, that nominal “series” is apparently very loosely connected, only by having main or other characters from the fictional Doucet clan; and a Doucet appears in this novel, though not as the protagonist. Our protagonists are sheriff’s deputies Nick Fourcade, a detective, and Annie Broussard, a uniformed deputy who’d like to be a detective. (The book is also counted as the opener of the Broussard and Fourcade series, which is apparently more connected; but it has a resolution to the mysteries involved in this volume, while leaving things open for new ones.)

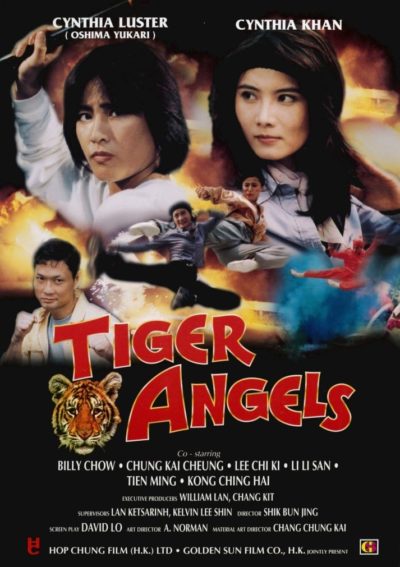

This is officially characterized (though not in the cover copy) as the fourth book of the author’s Doucet series. However, that nominal “series” is apparently very loosely connected, only by having main or other characters from the fictional Doucet clan; and a Doucet appears in this novel, though not as the protagonist. Our protagonists are sheriff’s deputies Nick Fourcade, a detective, and Annie Broussard, a uniformed deputy who’d like to be a detective. (The book is also counted as the opener of the Broussard and Fourcade series, which is apparently more connected; but it has a resolution to the mysteries involved in this volume, while leaving things open for new ones.) It is pretty close to an article of faith that no movie starring Yukari Oshima and Cynthia Khan can ever be entirely worthless. This film, however, shakes that belief to its very foundation. Not least because despite the cover and credits, found just about everywhere (including here), it barely stars them – indeed, Khan doesn’t even show up for the finale, with absolutely no explanation provided. This is included here, mostly as a warning, and because I’m a stickler for completeness with regard to their filmographies. Though in this case, I suspect, I’m less a stickler and more the sucker.

It is pretty close to an article of faith that no movie starring Yukari Oshima and Cynthia Khan can ever be entirely worthless. This film, however, shakes that belief to its very foundation. Not least because despite the cover and credits, found just about everywhere (including here), it barely stars them – indeed, Khan doesn’t even show up for the finale, with absolutely no explanation provided. This is included here, mostly as a warning, and because I’m a stickler for completeness with regard to their filmographies. Though in this case, I suspect, I’m less a stickler and more the sucker. There seems to have been a sudden surge of gynocentric takes on Taken (as it were), with first

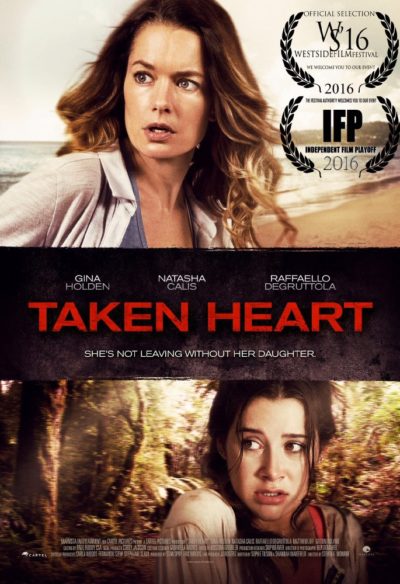

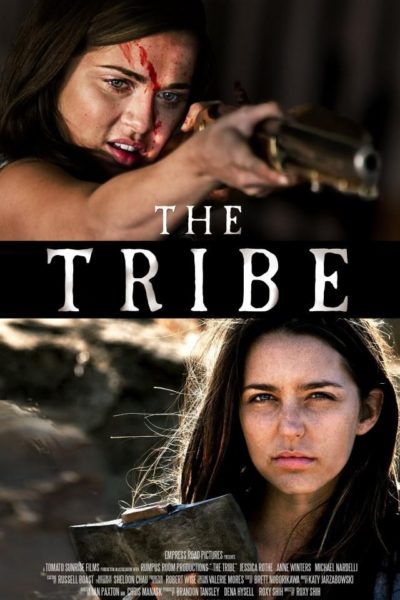

There seems to have been a sudden surge of gynocentric takes on Taken (as it were), with first  Disease has wiped out most of civilization, and left those who have survived, scrambling to cope. Better equipped than most are sisters Jenny (Rothe), Sarah (Winters) and silent little Danika (Jones). For their father was a doomsday prepper, who created a “bug out” cabin in the desert, stocked with all the necessities to survive. However, neither he nor their mother are around any longer: the former died during the crisis, and the latter went out to seek help and never returned. So it’s all down to the sisters, who have been reminded about the golden rule, time and again, by their Dad: do not let anyone in, under any circumstances.

Disease has wiped out most of civilization, and left those who have survived, scrambling to cope. Better equipped than most are sisters Jenny (Rothe), Sarah (Winters) and silent little Danika (Jones). For their father was a doomsday prepper, who created a “bug out” cabin in the desert, stocked with all the necessities to survive. However, neither he nor their mother are around any longer: the former died during the crisis, and the latter went out to seek help and never returned. So it’s all down to the sisters, who have been reminded about the golden rule, time and again, by their Dad: do not let anyone in, under any circumstances.

A bus full of Japanese schoolgirls includes the quiet, poetry-writing Mitsuko (Triendl), who drops her pen. Bending down to pick it up, she thus survives the lethal gust of wind which neatly bisects, not only the bus, but the rest of her classmates. Ok, film: safe to say, you have acquired our attention. [Not for the first time the director has managed this: the opening scene of his Suicide Circle is one we still vividly remember, 15 years later]

A bus full of Japanese schoolgirls includes the quiet, poetry-writing Mitsuko (Triendl), who drops her pen. Bending down to pick it up, she thus survives the lethal gust of wind which neatly bisects, not only the bus, but the rest of her classmates. Ok, film: safe to say, you have acquired our attention. [Not for the first time the director has managed this: the opening scene of his Suicide Circle is one we still vividly remember, 15 years later]

Kate’s (Brook) life has fallen apart: she has just been told the store she works at is closing because the owner is cashing in on a redevelopment offer; her boyfriend has dumped her; and Kate’s attempt at suicide by gas oven is doomed since she failed to pay the bill. What’s a girl to do? The answer is apparently, take inspiration from her heroine, Bonnie Parker. But rather than robbing banks, Kate teams up with her other disgruntled work colleagues, hatching a daring plan to copy the key to the store, seduce the safe combination out of the firm’s accountant, Mat (Williams) and plunder the ill-gotten gains.

Kate’s (Brook) life has fallen apart: she has just been told the store she works at is closing because the owner is cashing in on a redevelopment offer; her boyfriend has dumped her; and Kate’s attempt at suicide by gas oven is doomed since she failed to pay the bill. What’s a girl to do? The answer is apparently, take inspiration from her heroine, Bonnie Parker. But rather than robbing banks, Kate teams up with her other disgruntled work colleagues, hatching a daring plan to copy the key to the store, seduce the safe combination out of the firm’s accountant, Mat (Williams) and plunder the ill-gotten gains.