I’ve noticed a clear trend over the past couple of years for action-heroines to skew younger. Both of the principal 2011 genre entries to date, Sucker Punch and Hanna have featured heroines who aren’t old enough to drink, particularly in the latter’s case. One of the most anticipated films, currently in pre-production, is The Hunger Games, in which a 16-year old girl is press-ganged into a fight to the death, against other teenagers. But we’ve seen examples previously too, notably in last year’s Kick-Ass, where a foul-mouthed moppet stole the film in many people’s eyes, albeit not without causing a great deal of controversy.

Let’s review these, and some other entries in the sub-genre, both historical and fictional. You can find them all the way back to the seventh century, such as China’s Princess Pingyang, who was born in 598, and was instrumental in raising and leading an army of 70,000 men in a successful rebellion against the Emperor Yang, before reaching her twentieth birthday. This helped establish her father as the first Emperor of the Tang dynasty, often regarded as a high-point of Chinese civilization. We can perhaps file Mulan in this category too, though the poem does not assign her a specific age.

Joan of Arc was perhaps the first world renowned teenage action-heroine. She led the French army at the age of 16 or 17, lifting the siege of Orleans and turning the course of the Hundred Years’ War in France’s favour, though it rumbled along for decades more. A little later in French history, Jeanne Laisné, known as Jeanne the Hatchet after a crucial role in preventing the capture of Beauvais by the Duke of Burgundy. Many countries have their own “Joans”, and sher may well have been an inspiration for Maria Rosa, a 15-year old girl who claimed divine visions and led a rebel army during the Brazilian Contestado War around 1914.

Joan of Arc was perhaps the first world renowned teenage action-heroine. She led the French army at the age of 16 or 17, lifting the siege of Orleans and turning the course of the Hundred Years’ War in France’s favour, though it rumbled along for decades more. A little later in French history, Jeanne Laisné, known as Jeanne the Hatchet after a crucial role in preventing the capture of Beauvais by the Duke of Burgundy. Many countries have their own “Joans”, and sher may well have been an inspiration for Maria Rosa, a 15-year old girl who claimed divine visions and led a rebel army during the Brazilian Contestado War around 1914.

Around the year 1660, we find the lyrically-named Görwel Christina Carlsdotter Gyllenstierna. Wikipedia tells us this Swedish noblewoman “was known by her contemporaries for her great learning as well as for her interest and skill within sports normally reserved for males.” She was referred to as “A Minerva and an Amazon in one”, and made herself widely known in her mid-teens, when she challenged a Lieutenant Colonel in the Swedish military to a duel – he had married her cousin against the consent of her family. I couldn’t find any record of the duel’s result, but she would certainly seem to qualify as an action-heroine.

A fairly notable case was that of Mary Ann Talbot (above left), who took a male name and joined the British Navy at age 14. to be with her lover. She was wounded twice and captured by the French before returning to London four years later. She only revealed her gender when a press-gang tried to re-enlist her forcibly, at age 19. She then became a servant in the household of a publisher, who subsequently published her memoirs. Another teenager to take this route around the same time, was 17-year old Anna Lühring, who fought in the Prussian Army as “Edward Kruse”, and remained with her unit even after her true identity was discovered.

Such tactics were necessary in Western society because of the increasing belief that women were not “fit” for combat. It was still possible as late as 1915, when Dorothy Lawrence (right) posed as a man to reach the Somme front-lines, where she laid mines, until illness forced her to reveal her identity. Her memoirs are available, free, from Google E-books. Finally, a couple of others about whom not much is known. Candelaria Figuerdo joined the Cuban revolutionary forces in 1868 at 16, and is said to be the first woman to fight in defense of Cuba. And Rayna Kasabova was a Bulgarian air force pilot and the first woman in the world to participate in a military flight. At 15, during the First Balkan War in 1912, she flew above Edirne to throw out propaganda leaflets in Turkish.

Such tactics were necessary in Western society because of the increasing belief that women were not “fit” for combat. It was still possible as late as 1915, when Dorothy Lawrence (right) posed as a man to reach the Somme front-lines, where she laid mines, until illness forced her to reveal her identity. Her memoirs are available, free, from Google E-books. Finally, a couple of others about whom not much is known. Candelaria Figuerdo joined the Cuban revolutionary forces in 1868 at 16, and is said to be the first woman to fight in defense of Cuba. And Rayna Kasabova was a Bulgarian air force pilot and the first woman in the world to participate in a military flight. At 15, during the First Balkan War in 1912, she flew above Edirne to throw out propaganda leaflets in Turkish.

The purpose of all this is to show that age, or lack thereof, is no impermeable barrier. Even when barely into the teenage years, and certainly too young to vote or drink, women are capable of courage and action. But it has long been a problematic in the movie world. While I wouldn’t claim it was the first of the genre, undeniably the most influential was Luc Besson’s Léon, a.k.a. The Professional. In this Natalie Portman played Matilda, a 12-year old who sees her whole family gunned down by a corrupt DEA squad, but has the good fortune to live next door to a taciturn assassin (Jean Reno) who takes her in – not without qualms on his part. She wants to become a ‘cleaner’, like him, so she can avenge her family, and launches a one-girl assault on the DEA headquarters. That triggers their head, the supremely-psychotic Gary Oldman, to marshal forces of his own, setting the scene for a truly memorable final battle.

It’s one of my all-time favorites, but a number of critics found the relationship between Matilda and Léon troublesome, such as Gene Siskel calling it “questionable in its would-be sexy portrayal of a pre-teenage girl.” Part of the problem is it is Matilda who tries to instigate a physical relationship, pouncing on the first thing anywhere approaching genuine affection that she has ever experienced – Léon isn’t much more emotionally-rounded, and has no idea how to respond, except for a vague feeling it’s not right. But it is, apparently, okay to train Matilda as an apprentice killer. These aspects were a lot more explored in the extended European version, which runs 25 minutes longer; the US version was edited after test audiences reacted badly to Matilda’s more adult activities.

One can look to Japan for other provocative examples, both live-action and animated. The origins go back well before that, however, to the sixties and the pinky violence genre, which combine sex and…well, violence. While not all such “bad girl” films necessarily involve teenagers, some would certainly qualify, such as the marvellously-titled Terrifying Girls’ High School: Lynch Law Classroom, which lobs horror elements into the mix. I hope to cover more from this genre in the coming year. But teenage terrors extend beyond this: others worth mentioning with characters who can kill you as easily as they’d go shopping include Azumi, The Machine Girl and Mutant Girls Squad. These all represent an interesting counterpoint to the rigid role models typically imposed on women in Japanese society, and their popularity may represent a rebellion of sorts against this.

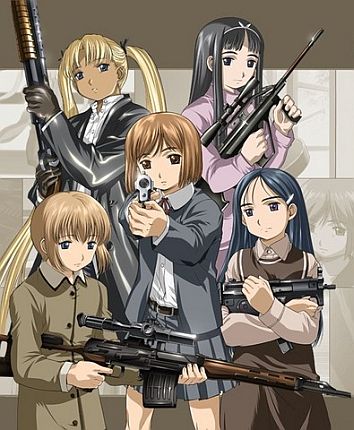

In a somewhat more light-hearted vein (for the most part), many anime and manga series have had teenage protagonists – as you’d expect, given they are often the core audience. The archetype goes back at least to the mid-1950’s, and Osama Tezuka’s Princess Knight, about a princess who must pretend to be male, so she can inherit the throne. There are too many of these even to list here, but some of the most well-known action-oriented examples in the West include Project A-ko, Sailor Moon, Blood: The Last Vampire, Cutie Honey, Gunslinger Girl (left), Noir and Dirty Pair – particularly Dirty Pair Flash, where both Kei and Yuri are seventeen-year olds.

In a somewhat more light-hearted vein (for the most part), many anime and manga series have had teenage protagonists – as you’d expect, given they are often the core audience. The archetype goes back at least to the mid-1950’s, and Osama Tezuka’s Princess Knight, about a princess who must pretend to be male, so she can inherit the throne. There are too many of these even to list here, but some of the most well-known action-oriented examples in the West include Project A-ko, Sailor Moon, Blood: The Last Vampire, Cutie Honey, Gunslinger Girl (left), Noir and Dirty Pair – particularly Dirty Pair Flash, where both Kei and Yuri are seventeen-year olds.

Probably the most notorious example of live-action is Battle Royale, which follows a class of 15-year olds as they are kidnapped by the goverment, put on a deserted island and ordered to kill each other, in order to strike fear into the rest of the nation’s youths. The results show that lethal intent is by no means limited to the male sex, and the film was condemned at the time of its release in late 2000, by some in the Japanese parliament as “crude and tasteless”, who also complained about the ‘R15’ rating, saying it was liable to harm teenagers. Rumour has it that it has been “banned” in the United States, but it’s more that the makers were concerned about possible US lawsuits, post-Columbine. The movie may eventually come out – in its 10th-anniversary, 3D version!- this year.

The movie is unquestionably an influence on The Hunger Games, a young-adult novel written by Suzanne Collins, now in the process of being made into a major film. In both the setting is sometime in the future, when the threat of chaos has forced the totalitarian government into tough measures: randomly selecting children to participate in a “kill or be killed” contest, televised nationally “pour discourager les autres”, as Voltaire almost once said. Collins has never acknowledged the similarities, and it’s possible she was unaware of underground cinema – but it’s hard to believe everyone who saw the manuscript was similarly ignorant.

My major concern is whether the film will be able to pack the wallop contained in some of the book’s sequences, while working within the PG-13 rating it’s aiming for. [I note the irony of the rating system: there’s nothing to stop teenagers from buying the books which describe, in bloody details, murder of and by children. But see those same fictional events acted out in a cinema? Not without an accompanying parent or guardian] One suspects the result will, inevitably, be watered-down: it will take some skill from director Gary Ross, to replace the visceral impact with a more emotional one. It’s certainly not the Twilight saga, which has sharply divided readers. Bella is too ’emo’ for many tastes, but the supporting characters provide some counterpoints to that argument. If you’re looking for strong female roles in that genre, forum contributor Yâoguài provided a useful introduction to some other entries worth a look.

Quick: name a film where Saoirse Ronan plays a teenage assassin – besides Hanna. She seems to have developed a taste for the genre, as she also plays one in Violet & Daisy, directed by Geoffrey Fletcher (the screenwriter for Oscar-winner Precious). She is Daisy, along with Alexis Bledel as Violet: the two young killers for hire accept what they think will be a quick-and-easy job, until an unexpected target throws them off their plan. Said Ronan, “They couldn’t be more different [from Hanna]. Daisy is a really, really sweet girl. She’s not a natural killer like Violet is… They have their own little world. And everything is poppy and fun and about puppy dogs and dresses. They’re taking on this job because they want to get this dress that their pop idol has. Her name is Barbie Sunday.”

Quick: name a film where Saoirse Ronan plays a teenage assassin – besides Hanna. She seems to have developed a taste for the genre, as she also plays one in Violet & Daisy, directed by Geoffrey Fletcher (the screenwriter for Oscar-winner Precious). She is Daisy, along with Alexis Bledel as Violet: the two young killers for hire accept what they think will be a quick-and-easy job, until an unexpected target throws them off their plan. Said Ronan, “They couldn’t be more different [from Hanna]. Daisy is a really, really sweet girl. She’s not a natural killer like Violet is… They have their own little world. And everything is poppy and fun and about puppy dogs and dresses. They’re taking on this job because they want to get this dress that their pop idol has. Her name is Barbie Sunday.”

On television, one show stands out above all others: Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which followed the life of Buffy Summers, through the discovery of her powers and on through college and into adulthood. But the first three seasons of the series (as well as the feature which preceded it) all took place at High School, and it’s there that the show’s foundations were laid – and some would argue, its best work done (certainly, the show received its best ratings). The influence of Buffy on the field has been enormous, with a slew of shows which owe a debt to her in one form or another, and it’s no exaggeration to say that the heroine became a cultural icon. Indeed, it found a success, both critical and commercial, which those involved have found somewhat hard to recapture. Joss Whedon’s subsequent forays into TV, in Dollhouse and Firefly, both were canceled due to low ratings, though the former has its own devoted cult following.

Even the most contentious of the above, however, were a mere blip compared to the – and there’s not really another word – shitstorm that greeted Kick-Ass last year, mostly for its tiny killing machine, Hit Girl (Chloe Moretz). The relationship is similar to that in Leon, except that it’s her father (Nicolas Cage) who is her tutor. And, while Matilda never actually kills anyone, Hit Girl does so with gleeful, foul-mouthed abandon. “Okay, you cunts – let’s see what you can do now,” she says, before taking apart an apartment full of drug-dealers and low-lives. When it comes to the action, she’s certainly a great deal more competent and confident than the hero.

But not everyone was impressed…

“Millions are being spent to persuade you that Kick-Ass is harmless, comic-book entertainment suitable for 15-year-olds. Don’t let them fool you… It deliberately sells a perniciously sexualised view of children and glorifies violence, especially knife and gun crime, in a way that makes it one of the most deeply cynical, shamelessly irresponsible films ever… The reason the movie is sick, as well as thick, is that it breaks one of the last cinematic taboos by making the most violent, foul-mouthed and sexually aggressive character, Hit-Girl, an 11-year-old.The movie’s writers want us to see Hit-Girl not only as cool, but also sexy, like an even younger version of the baby- faced Oriental assassin in Tarantino’s Kill Bill 1. Paedophiles are going to adore her. One of the film’s creepiest aspects is that she’s made to look as seductive as possible… She’s fetishised in precisely the same way as Angelina Jolie in the Lara Croft movies, and Halle Berry in Catwoman. As if that isn’t exploitative enough, she’s also shown in a classic schoolgirl pose, in a short plaid-skirt with her hair in bunches, but carrying a big gun. Kick-Ass is not the harmless fun it pretends to be. Yes, it’s lightweight and silly, but it’s also cynical, premeditated and mindbogglingly irresponsible. And in Hit-Girl, the film-makers have created one of the most disturbing icons and damaging role-models in the history of cinema.”

Even for the most reactionary critic on the most reactionary newspaper (The Daily Mail) in the UK, that’s harsh – and largely unjustified. There’s very little sexual about Hit Girl at all; the hero has absolutely no interest in her (being keener on a girl who thinks he’s gay!), and she’s almost entirely no-nonsense and practical. The only possible exception is the scene where she dresses in the schoolgirl uniform shown atop this piece to get into the villains’ headquarters, and that’s exploiting the vulnerability of the image than its sexuality. But guess which pic, of all the dozens possible from the movie, is used to illustrate the review on Tookey’s own website? Yep. The same. He’s happy to condemn, while simultaneously exploiting it for his own moral agenda.

But his reading of the movie says a lot more about the writer than the film: as another critic mentioned, “If anyone finds her sexy. it’s because they find little kids sexy”. And the truth finally came out, as Tookey admitted (in the unrepentant review linked above) to having “experienced at first hand the attentions of three different men who would now be called paedophiles.” Three? As Oscar Wilde nearly put it, “To be molested once may be regarded as a misfortune; three times looks like carelessness.” It’s a known fact paedophiles were usually themselves abused as children, so I have absolutely no problem in calling Tookey out for expressing his tendencies in this area: put bluntly, I’d not leave my kids alone with him. And he was somehow surprised by the backlash?

But his reading of the movie says a lot more about the writer than the film: as another critic mentioned, “If anyone finds her sexy. it’s because they find little kids sexy”. And the truth finally came out, as Tookey admitted (in the unrepentant review linked above) to having “experienced at first hand the attentions of three different men who would now be called paedophiles.” Three? As Oscar Wilde nearly put it, “To be molested once may be regarded as a misfortune; three times looks like carelessness.” It’s a known fact paedophiles were usually themselves abused as children, so I have absolutely no problem in calling Tookey out for expressing his tendencies in this area: put bluntly, I’d not leave my kids alone with him. And he was somehow surprised by the backlash?

This is by no means an exhaustive survey. I could have gone on at quite some more length. Hanna. True Grit. Let the Right One In. But it does reflect, to some extent, the way society views teenage action heroines, because they are even more transgressive that adult action heroines. Women aren’t “supposed” to be assertive, self-confident or prepared to battle, physically, for what they believe. The same is true for children. Combine the two and – despite the examples drawn from history given above – you’ve got something which pushes a lot of society’s buttons. And I suspect that’s not something which is likely to change anytime soon.

See also:

- 13 Frightened Girls!

- Abigail

- After the Pandemic

- Angelbound, by Christina Bauer

- The Archer

- Assassinaut

- Azumi

- Barely Lethal

- Becky

- The Blind Spot, by Michael Robertson

- Blood +: Episodes 1-25

- Blood: The Last Vampire (animated)

- Blood: The Last Vampire (live-action)

- Bloodbath at Pinky High, Part 1

- Bloodbath at Pinky High, Part 2

- Bloody Chainsaw Girl

- Book of Monsters

- The Breadwinner

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer (film)

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer: season two

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer: season six

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer: season seven

- Cattle Annie and Little Britches

- Chastity Bites

- The Circle (Cirkeln)

- Cold November

- Counterfeiting in Suburbia

- Crimson, by Arthur Slade

- The Darkest Dawn

- Darkness on the Edge of Town

- Deidra and Laney Rob a Train

- The Dirty Pair

- E.M.P. 333 Days

- The Eagle Huntress

- Eko Eko Azarak

- Enola Holmes

- Enola Holmes 2

- Fair Game (1982)

- The Feral Sentence by G. C. Julien

- Final Girl

- Fugitive at 17

- Girl of Fire, by Norma Hinkens

- Go For Broke

- Grand Theft Auto Girls

- Grave Mercy, by Robin LaFevers

- Gunslinger Girl

- Hanna

- Hell’s Fury: Wanted Dead or Alive

- High School Girl Rika: Zombie Hunter

- High School Hellcats

- Homestead

- How I Live Now

- The Hunger Games (film)

- The Hunger Games: Catching Fire

- The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1

- The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2

- Hunter, Warrior, Commander by Andrew Maclure

- The incredible, true survival story of Juliane Koepcke

- Into the Dark, by J.A. Sutherland

- Joan of Arc: History vs. Cinema

- Justice High

- Kill La Kill

- Killer K

- Kim Possible

- Kite

- Kite (live action)

- Kyoko vs. Yuki

- The Last Dragonslayer

- The Last Survivors

- Lethal Dispatch, by Max Tomlinson

- Locked Up

- Maidentrip

- Miracles Still Happen

- Molly

- Mutant Girls Squad

- My Day

- Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

- Nightblade: A Book of Underrealm by Garrett Robinson

- No Safe Haven, by Kyla Stone

- The Poppy War, by R.F. Kuang

- De Prooi

- Prospect

- Resilience and the Lost Gems

- A Resistance

- Riddle Story of Devil

- Rina Takeda: The Next Action Heroine?

- Riot Girls

- Run Hide Fight

- RWBY

- Sailor Suit and Machine Gun

- Sailor Suit and Machine Gun: Graduation

- Sexy Battle Girls

- Shadow Corps, by Justin Sloan

- Sket

- Sucker Punch

- Sugar & Spice

- The Sun At Midnight

- Switchblade Sisters

- Teenage Bank Heist

- Teenage Hooker Becomes a Killing Machine

- Tokyo Ballistic War

- The Tribe

- True Grit

- Vesper

- Violet and Daisy

- Viral

- War Witch

- Warchild: Pawn, by Ernie Lindsey

- Wendy Wu: Homecoming Warrior

- Wicked Blood

- Wilderness Survival for Girls

- Winter’s Bone

- The Witch Files

- The Witch: Part 1. The Subversion

- The Wrath of Becky

- Yasmine